Writer and historian Valentin Groebner describes his experience with “the cruise ship of the highway” in the Greek countryside.

The pandemic does not rule out holidays; at least it didn’t last year. Coupled or with the kids, last year we travelled in private bubbles and visited places we’d been before – it was not a time for experimentation. Mostly by car, though. Hotels and parking lots were full to capacity. So were the campsites: the entire household on wheels; everywhere. Suddenly there was a pervasive desire for a road trip. Of course there was before, but in the complicated year of 2020, conversations about planned trips would unusually often start like this: Instead of a house by the sea or a hike in the mountains, we wanted to go on a great escape. I felt that way, too. I didn’t know exactly where I wanted to go. I just felt like being on the road all the time. I imagined it empty, lonely and wild, with high mountains and a view of the sea. And there I was.

Greece, Peloponnese: mountains everywhere, rocky capes and endless spectacular views. The motoring would suddenly halt, only to resume again at a walking pace. Gear down. Second. First.

The essence of travel is not the holiday destination you have been longing for per se. The true essence of the journey is the others who travel. They stood there, with their square blocks, up the narrow curving streets along the coast, facing the famous village of Leonidio: five or maybe six caravans. Neither would they come near to one another, nor would any other vehicle approach them. Only while stuck in a traffic jam, one can discern the true essence of the journey; in these dull moments of such close proximity, one can finally notice. In the field of travel, traffic jams reflect the genius of the swarms: a magnifying glass that travellers turn on themselves. I was still; everyone was still; and so, I could quietly reflect on the sign ‘No hurry’ hung on the back of the caravan in front of me; Swedish car plates.

A few things learnt in traffic jams: German caravans differ from their -equally many- Swiss, Dutch and French counterparts because of their need to make statements. Namely, German caravans always bear large signs on the back, carrying messages, addressed to fellow drivers, such as: “Too old to work/Too young to die… goodbye!”, “Relax”, “I’m on a road trip”, “Smouts”. This is what autonomy looks like from the back. “All these benevolent people do the same as me” I thought, as I sat there motionless, in my slightly bigger box than the others’. Everywhere I went in 2020, RVs and Camper Vans had arrived first. All these people had taken to the road, inside their own cinema; their own space capsule with the big (wind)screen in front. Instead of a home cinema, here’s a cinematic house. Not apparent at first glance in today’s caravans, yet, the latter were created by the artistic avant-garde of surrealism in its most luxurious version. The first caravan was built in 1925 by the wealthy eccentric writer Raymond Roussel, a friend and role model of André Breton and Michel Leiris. It was nine metres long and had a bathtub. In this Villa Nomade, Roussel travelled the following year from Paris to Rome and was received by Mussolini and the Pope himself. And while Roussel’s journey received extensive media exposure, with exclusive coverage in a French magazine, caravans only became increasingly popular from the 1930s onwards, and particularly in Germany. They were called Ark, House for Life, Portable House. “With this caravan,” wrote its builder Hans Berger proudly in 1938, “the German mobile home movement has taken off.” And he went on: “Now it is advancing unstoppably, like an avalanche.”

The models that followed were called Caravan, Big Caravan or Cabin, as appropriate. Berger’s illustrious success story acquired the pompous title of the Avenue Yacht. Is this the basis of the slightly compelling desire of the Germans to give their privately owned vehicles of traveling bliss the fanciest names possible?

“Yes, it’s difficult with the caravans,” said the Greek senior, when we finally arrived at the bar in Leonidio. “There didn’t used to be so many.” He had worked all his life in Pforzheim, Germany, and now he was back here, on the edge of the Peloponnese peninsula. “And then they started to multiply, year after year.” At one point he began to think they looked like tanks from an occupying army, like war vehicles on the beach. “Only now, this army,” and here he laughed, “is made up of almost exclusively retired people, old men like me.” And now? “Look at them. Most of them are white. Like care homes for two. They are staying in their ambulances.” 1.8 million Germans owned a caravan or Camper Van last year; in 2015 there were half a million fewer. Parked one behind the other, these vehicles of freedom would create a queue ten thousand kilometres long, four times the distance from Pforzheim to Leonidio. “Freedom on four wheels” was the advertising slogan for the most commercially successful Camper Van.

“Freedom, here we come” is the – slightly threatening – slogan on the website of the largest German manufacturer of caravans and camping vehicles, which in the year 2020 managed to double its sales in the city vehicle category, as proudly stated. The editors of Womoblog, which is aimed specifically at caravan owners, know that more than well.

“The basic problem of transmission,” they say, “doesn’t even exist in caravans. With your household as both point of departure and arrival, any contact with strangers is practically out of the question.” This kind of travel is “very friendly during the coronavirus season,” they added in an interview with a Swiss newspaper. The caravan is not the yacht, but the cruise ship on the Boulevard – no risk of transmission, your bathroom and bedroom always nearby. “Now all the affluent young couples, the ones with ecological sensibilities, education and two salaries, could take it with them”, said the doctoral candidate in Ethnology at dinner. Their own Camper Van; the same one for all, which of course they could get it in a Beach, Coast or Ocean model, though somewhat expensive. The rest can be seen on social media, in countless photos taken with self-phones, all showing the same thing: a couple, their Camper and the sunset. But never the traffic jams. The Stallersattel region is a small border crossing from Austria to the Pustertal in South Tyrol. The crossing in the Italian part is a winding uphill road like a pin, only opening for fifteen minutes every hour and only towards one direction. When I got there, on a July morning, there were four Camper Vans in line waiting. At the point of the crossing three more; apparently they had been there all night.

“It makes sense for them to come to us,” said the innkeeper in Sexten, on the other side of the Pustertal. In densely populated Europe, caravans are a promise of freedom close to nature. She tells us she has the impression that never before have so many been on the road as much as in the peak summer of 2020. “They want an overnight stay with a view of the Dolomites. And, of course then they want to send photos from there.” Photos of camper vans on the Three Peaks of Lavaredo even appear in the campaign of the South Tyrol Tourism Board, although camping is banned there. “But we have three nature parks and that’s why they ride their castles and come here.” The traffic wardens in South Tyrol, meanwhile, have their own line about these square boxes of freedom: “They’ll drop a suitcase on the road again”.

Yet, it is also attractive; carrying everything with you, in constant motion; just us, our WC and the sunset. In practice, however, they’re rarely alone.

“Truth is found when you are stuck in traffic; or when you’ve lost your way”

Valentin Groebner

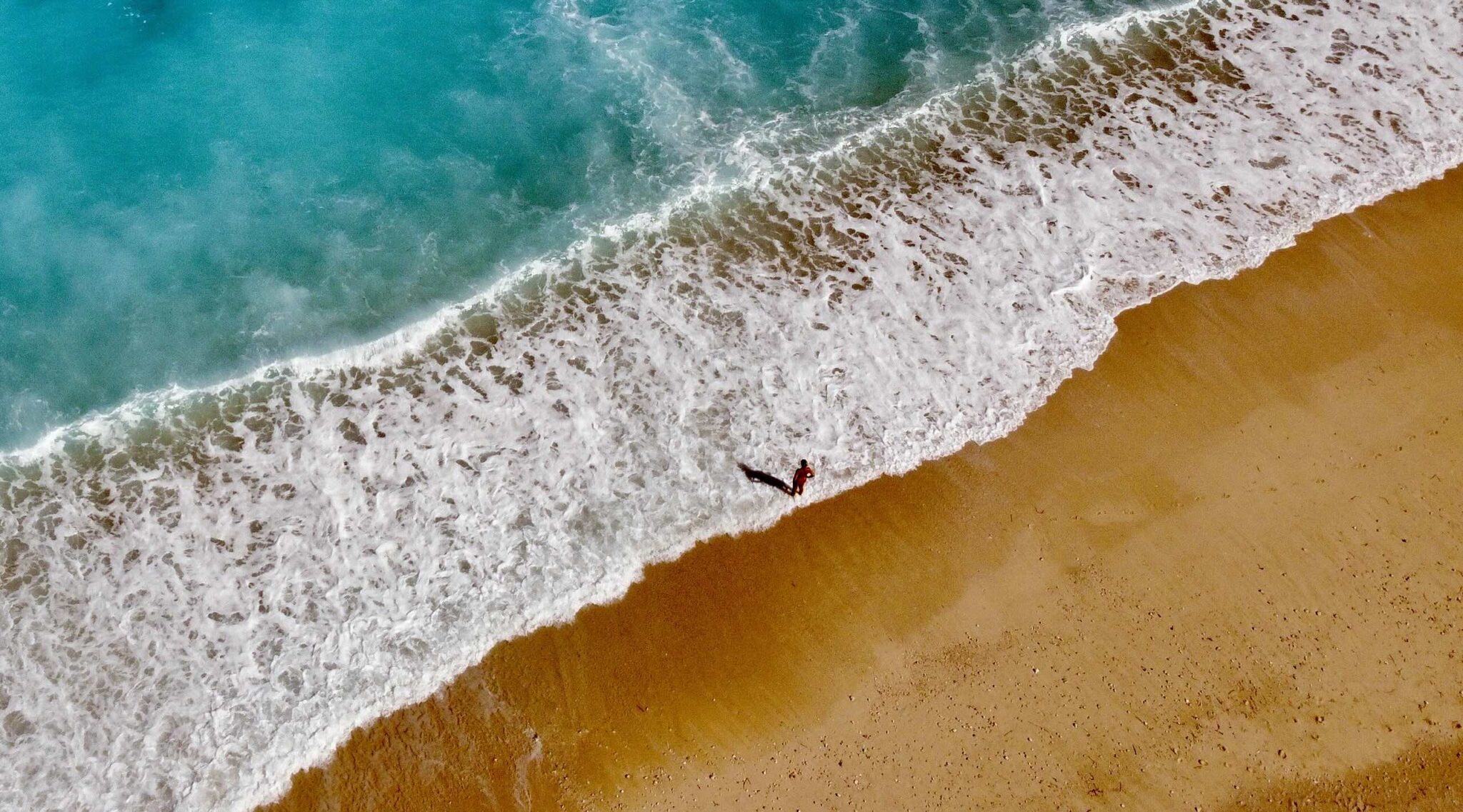

The beach at Kalo Nero was endless; pale sand with pebbles, a protected area. The caravans – one model called Pure, another Clever, a third Freetec S – formed little castles of cars among trees overlooking the sea. One could see them in exactly the same formation as early as 1969 in the comic strip Asterix in Spain – always in the shade and at a discreet distance from the beach bars.

One bar was called Karetta, like the Greek sea turtle, the other Cool, and together they made the promise of a holiday come true. You can consume pristine nature by participating in its rescue. And at the same time feel again in a magical way. Is that why caravans need to have such resounding names? Adria, Clever and Marco Polo, Silbersand and Edelweiß, Sun Living and Laika – the first creature sent into space, inside a Russian rocket. What happened to this dog?

I thought I should do a poll of all the owners of these trailers. What do they like? If they could travel anywhere, why did they come and stay here, on this very beach? What do they feel responsible for? But it wasn’t easy at all. The caravan couples were surrounded by some kind of aura, or should we call it an energy field? There was a “Make room please for this so special duality of ours” veiled, but clear attitude over all those vehicles, from Caravell to Weinsberg, all those tanks of privacy.

“Keep your distance” was the signal the two pensioners were sending out, silently at first, clearly afterwards, when they went out in the morning in shorts to walk the dog. They’d go: “What do you want? Oh no, please.”

Their real travel destination was not a place anyway, but an interval. A top German publisher’s top title in the fall of 2020 was taken from the novel Volkswagen blues – about one of literature’s finest couples traveling from Quebec to San Francisco in an old bus.

“A hymn to the Infinite”, wrote one review; “a road trip” another, “intelligent, light and melancholic at the same time”. British music critic Mark Fischer called pop music released from the late ’70s and ’80s “nostalgia for the future”, a future that had only existed in the form of its announcement in the past. Now, one year on from the start of the pandemic, everyone is feeling nostalgic for that kind of nostalgia. Camper Van would so much like to be pop, just like the novel in question. The book was first published in 1984.

Holidays always go together with a name that evokes magic. Bucaneer is the name of a company that produces camping vehicles – it’s amazing how wealthy tourists imagine themselves as pirates. Another is called Crosscamp – have they read “Notes on Camp” by Susan Sontag? A third, for lovers of the good Mediterranean life, is called Etrusco. But did I, too, not make my trip to the Peloponnese enchanted by the occult names of these lands? Even the administrative regions sounded like enticing promises here; Arcadia, Messinia, Laconia. The names of the locations turn out to be even more passionate. Megalopolis was certainly not as big as I imagined, but Paradisi was indeed very idyllic. Archangelos and Demonia were only a few miles away. Or maybe I should have gone to Metamorphosis, another hour down the road, passing through deserted narrow streets, where you feel like you’re at the end of the world?

Truth is found when you are stuck in traffic; or when you’ve lost your way. Without GPS, in my second-class rental car – damn my stinginess – the roads were getting narrower and narrower and the signs were getting sparser and sparser, and in between you only saw sketchy ones, hand-written on boards and nowhere a person to ask. After turning twice blindly, I found myself in absolute nowhere. It was beautiful there, huge chestnut trees, birds of prey circling, high cliffs and desolation. When I managed to read the signs again and compare them with the map, I realised I was now on the other side of the mountain. Not all the houses in the village seemed to be occupied, some were crumbling down. But at the entrance and exit to the area an ancient statue had been erected that looked brand new, slightly oversized, made of white stone and dressed in those tight-fitting sheets that all these statues wear and which look like wet cloth: a woman in a proud, rigid pose, sitting with a book· a sitting man with a beard. The fields were full of yellow crocuses. I turned off the engine. It was utterly silent, such that you could hear the shepherd with his sheep a hundred yards away, talking on his cell phone in Arabic. And the place was called, and no one would believe me, Karyes.

“Refugees work everywhere here”, the friendly Greek woman at the reception desk of the hotel in Kalamata told me the next morning. “But we ourselves are all children of refugees.” She herself had been born in Canada, the child of Greek immigrants; her family was forced to go there in 1948, after the Civil War. Now she had returned. “Those were hard years,” she said with a sigh. “But even harder for refugees.”

Kalamata, on the southern tip of the Peloponnese, is a lively and friendly city. A huge beach on the outskirts of the city and above it the high peaks of the Taygetos Mountain range. Behind, to the southeast, the Mani peninsula with its blue silhouette shone in the morning light. I thought that maybe this whole obsession with taking the roads unrestrainedly in caravans and Camping Buses has nothing to do with American road movies or with cinema, pop culture and corona virus. How high is the percentage of Germans with refugee experiences in the last two generations? When I left the hotel, three more caravans passed in front of me. One had a sign that read “Freedom”, another “Red Riding Hood”. On the road to Mani, all caravans had German plates. “Because of its rugged character,” read Wikipedia, “this mountainous peninsula has always been a haven with its own special culture: Free, wild and unpredictable.” Caravan owners are the moving micro-investors of holiday bliss. Their freedom lies in the fact that they assume minimal responsibility towards their nostalgia destination.

*Published in FAZ (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) on 18 February 2021. The article was translated by Elias Triantafyllou.