Even since the War of Independence, when it took a leading role in overthrowing Ottoman rule, Hydra has always been a stage for legends. The island’s steep cobblestone steps once carried musical legends, poets with notebooks stuffed in their pockets, and painters chasing the vibrantly elusive, mercilessly beautiful light.

Among those who stayed, who truly folded their lives into Hydra’s story, is the German artist Angelika Lialios Freitag. From bohemian Hydra in the 1970s to her flower canvases and collages today, Angelika has lived the island’s shifting seasons of art, beauty, and freedom. She first arrived in 1972, young and restless, and has been shaping art—and being shaped by the island, Greece, nature and life —ever since.

The Road to Greece

Before Hydra ever entered her life, Angelika was already chasing images. At the Werkkunstschule in Wiesbaden, she dabbled in everything—graphic design, illustration, photography, sculpture—hungry to try it all. “It included basically everything,” she says. “I chose graphic design, but we could join illustration classes and do new drawings.”

When her studies ended, she packed up her little car with a friend and drove through Yugoslavia toward Greece. “We had read about Hydra—that there were many artists, and that the Athens School of Fine Arts had its residence there,” she recalls. “Greece was the land of culture—the Acropolis, the statues, Athens.” Her friend, expecting marble gods to line the border crossing, was disappointed to see only mountains. Angelika laughs at the memory: “She asked, ‘Where are the statues?’”

They tried Poros first but found it uninspiring. Crossing the strait to Hydra, they landed in a world that felt different—smaller, rougher, but electric. She remembers walking into private exhibitions in people’s homes, pencil drawings pinned to walls, paper collages passed around like secrets. “I met all these people and so the next year we went straight to Hydra for three weeks and that’s when I met a Norwegian writer called Felix and he introduced me to George and that was that. We clicked immediately and then I came back and he came to Germany and it went back and forth.”

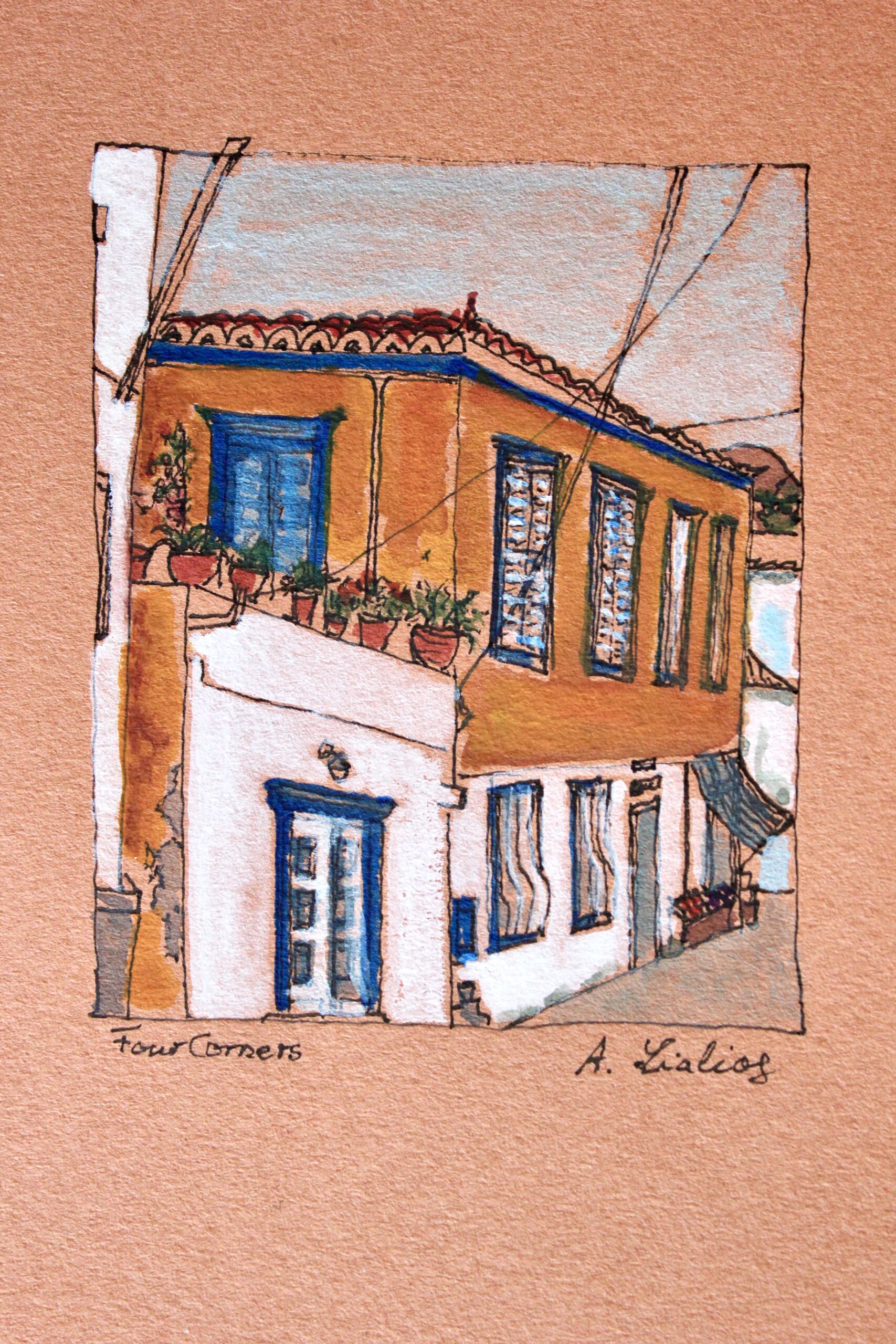

“I didn’t draw then,” Angelika says. “I ran a fashion boutique in Germany with designer clothes and I began drawing towards the end of the ’70s. I bought my etching press from a German company—80 kilograms!—that was transported to the house by donkeys and I started doing etchings and very small drawings which I colored with watercolor. I had my first exhibition at Loulaki Gallery which at the time was where now is a hardware store on Kala Pigadia and they had a gallery.”

Hydra in its Prime

The Hydra Angelika discovered was far less polished than it appears today, affordable, and exhilarating. Some of its grand houses were half in ruins, and rents were low enough that foreign writers and painters could stay through winter. “The foreigners in Hydra were eccentric—writers, painters,” she remembers. “The Hydriots kept more to themselves, but the foreign community was very lively. People invited each other into their homes, and it was inspiring.”

The island’s reputation for decadence, she insists, is mostly myth. “It’s quite overrated. You could say London was decadent or anywhere was decadent at that time. People were hippies. They were jumping in the fountains in Trafalgar Square. They were swimming here nude and the bishop went crazy. They were drinking till dawn at Bill’s bar and diving off the rocks at the Yacht Club. Some were smoking weed because they were on the way to India or somebody came from India and brought a little bit, but it’s exaggerated now. It was a much freer lifestyle. They were sitting in the coffee house making bets on how long a marriage would last and of course it didn’t last because everybody was flirting with everybody.

“We didn’t have mobile phones; we went down to the port and actually met people. Leonora, whose former lover was the Cuban military officer and dictator Fulgencio Batista, used to host huge meals because the food was so cheap. You could invite 10 people and pay 100 drachmas. You could have five drinks an evening and you wouldn’t go bankrupt. Bill Cunliffe, (of Bill’s Bar), once brought caviar and salmon from Geneva and opened a bottle of champagne in his bar for everybody, and he held some exhibitions there which sold out. It was just fun.”

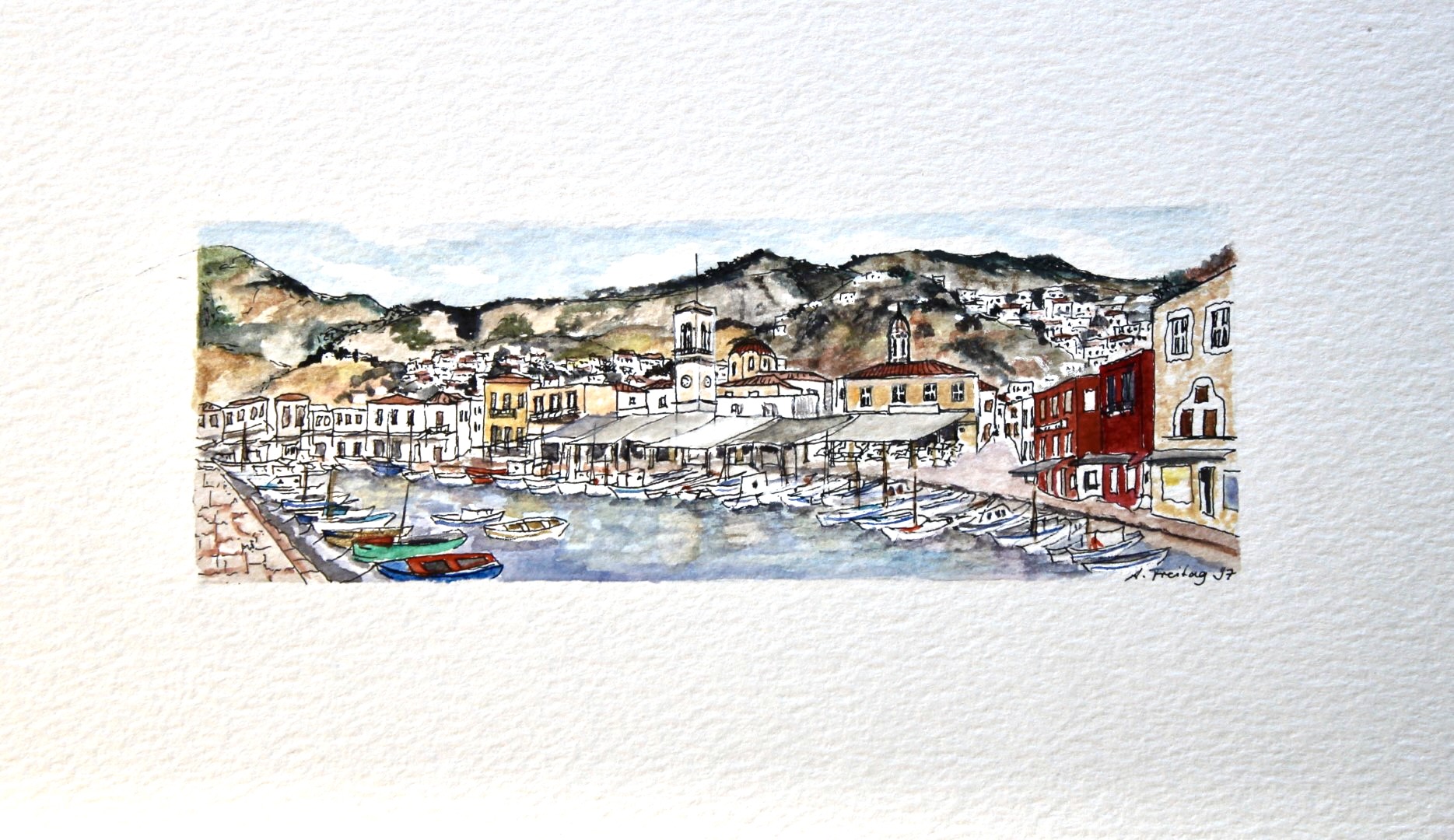

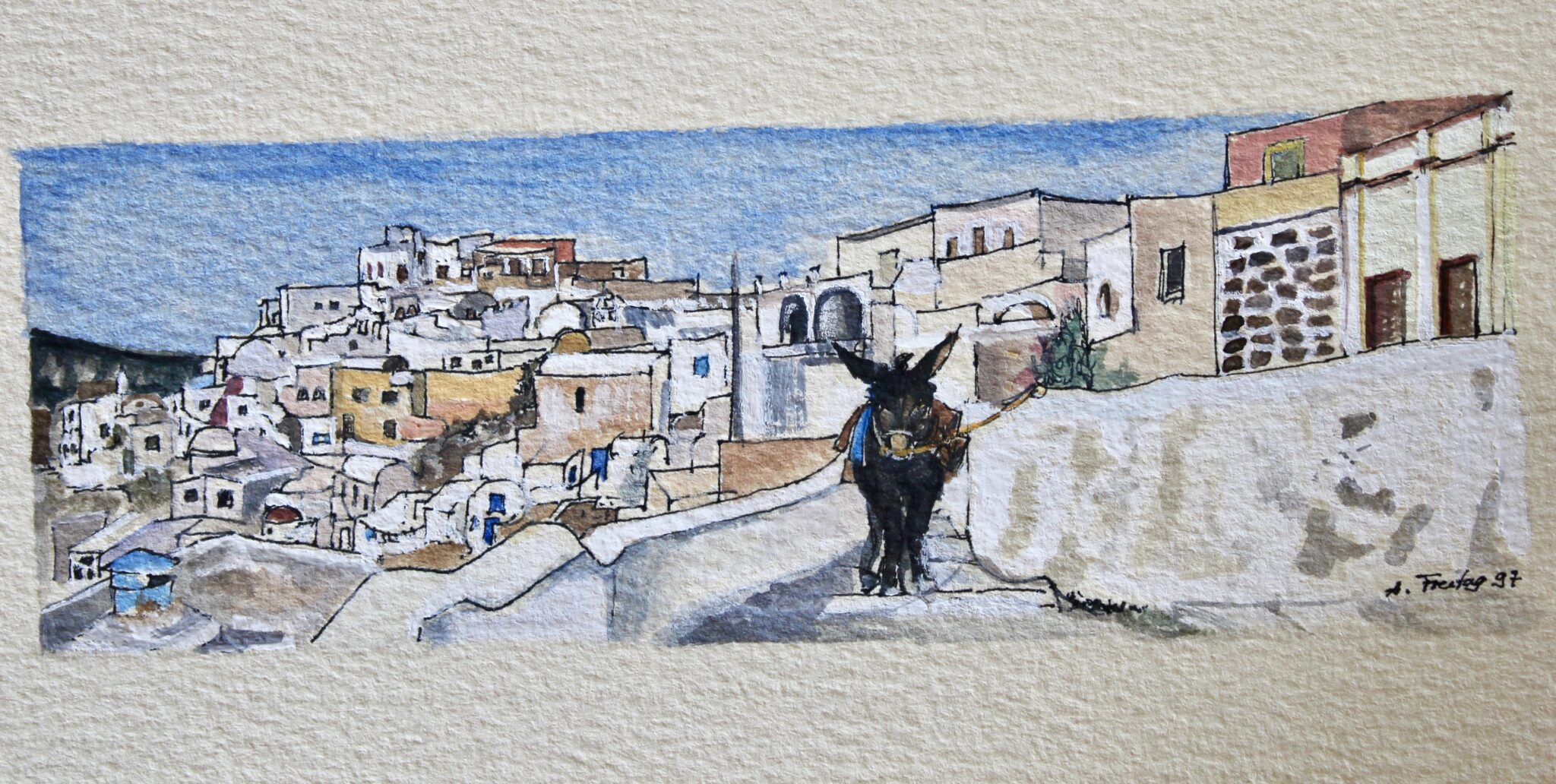

Angelika’s first works on the island were tiny etchings—domestic details, painted doors, hand-lettered market signs, steps glowing white with fresh limewash. She tinted them with watercolor, making each version slightly different. “It was much more colorful then, much more fantasy,” she says. “Those etchings became a picture of a time that has already vanished.”

Between Art and Family

By the 1980s, Hydra had claimed her fully. “My first exhibition came in 1985, just before my daughter Kai was born. The second followed in 1989, and by 1994 I was showing much larger watercolours at the municipal hall. Two of my biggest pieces were bought by a professor of architecture—they remain on Hydra, even though he later sold the house that held them.”

Over the years Angeilka’s work grew larger and bolder, yet her rhythm was dictated as much by family as by art.“If you look at painters, you hardly find famous women who also had families,” she reflects. “For me, family always came first. That meant I had to stop, then start again at a different point, often in a different style.”

Things changed when she moved to Athens in 1991 so her daughter could attend the German school. “After that, we came to Hydra only at Easter and in summer. My art shifted too—the works became larger. In Athens I had access to bigger sheets of paper and all the materials I needed, whereas on Hydra everything had to be small enough to carry. I could finally leave watercolors on a scaffold over winter without the paper crinkling, and that made a huge difference.”

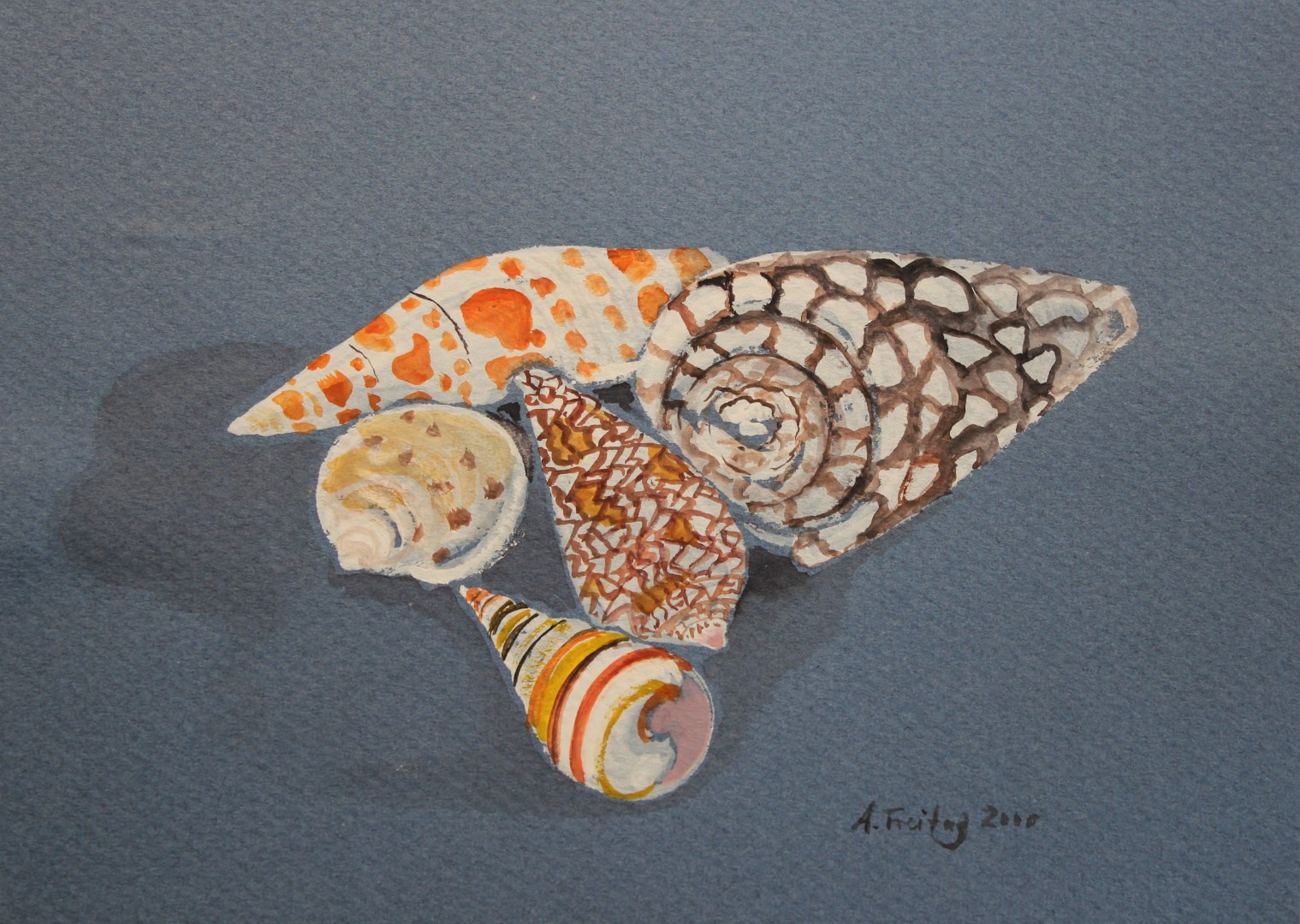

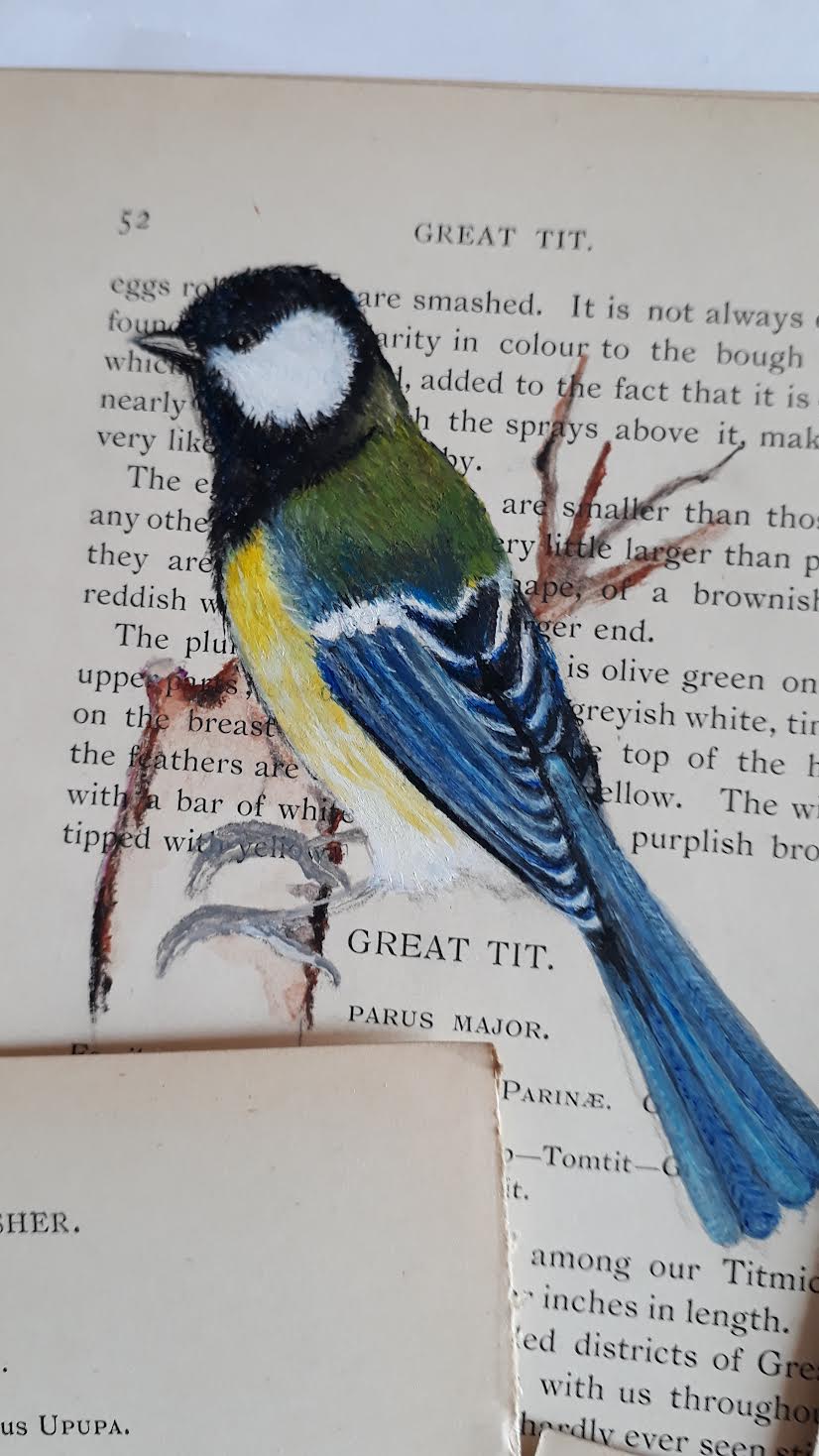

Hydra’s landscapes gave way to different forms of expression. “When the children were small, I turned to photography, and that began to influence the way I painted. Around 2000 I started painting flowers—first small acrylics on canvas, then larger works as the flowers themselves became more abstract. I was exploring light and color, always what fascinated me most. Art is about mood, light, beauty. It’s how something makes me feel.”

“When we moved from an apartment into a house with a garden at the end of the ’90s, I became captivated by the petals, the texture, the way light passed through them. By the time we moved to England in 2009, I had begun my ‘Garden Series.’ I studied botanical painting at Kew Gardens, joined the Botanical Society and the Miniature Society, and embarked on a trilogy of large garden canvases, each one taking a year. I still love those. When we returned to Greece in 2019, I continued painting flowers but also returned to watercolors and small drawings.”

A World Transformed

As her art evolved, so did Hydra. By the 1990s, the bohemian outpost had shifted into something far glossier. Mansions were restored, prices climbed, tourists started to return more frequently, and the artists who once squatted in crumbling rooms were replaced by high-end collectors and curators. “The romantic side is a myth of the past,” Angelika says. “Hydra is still an art island, but in a different way.”

Retrospective and Continuation

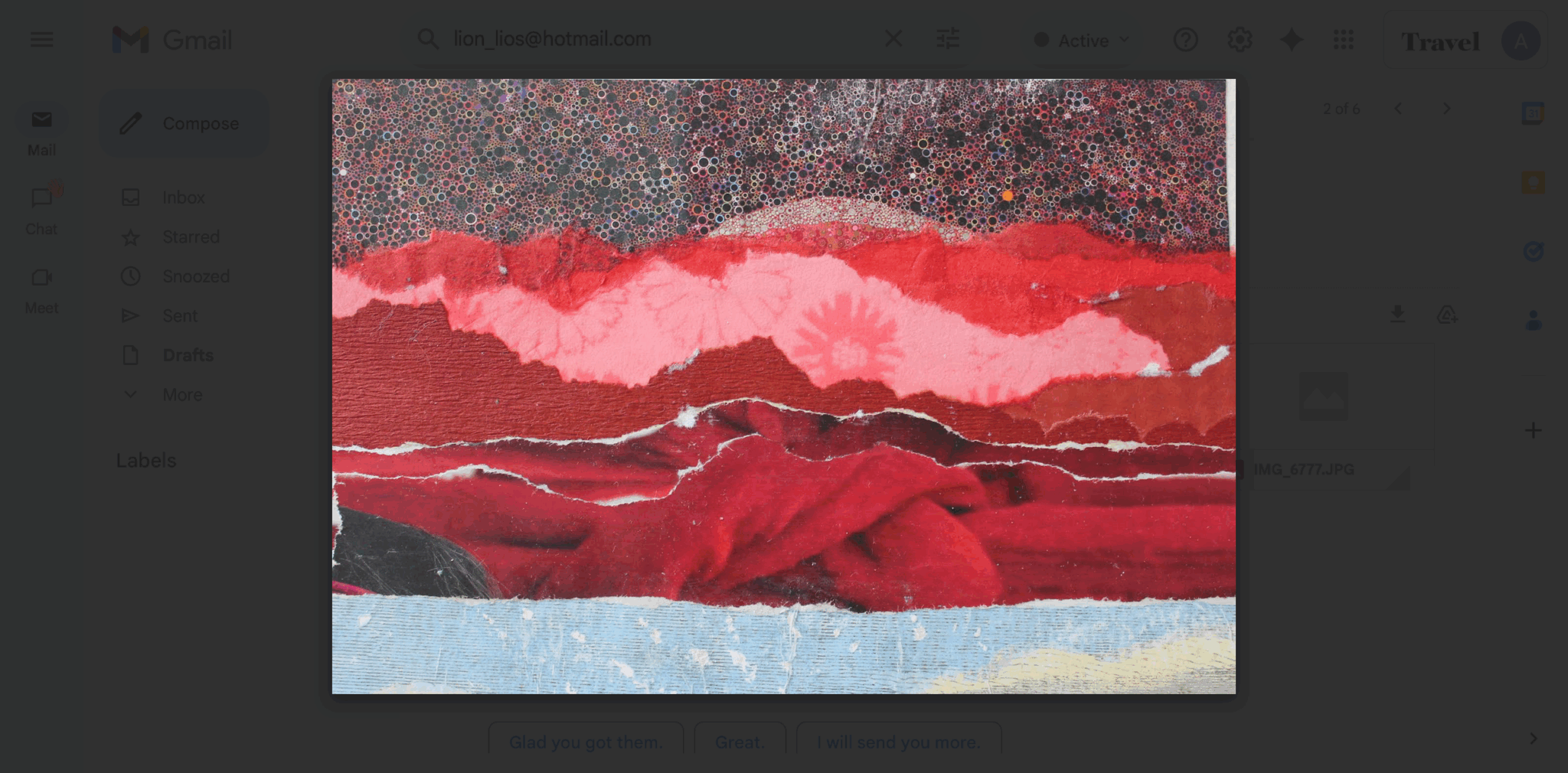

In 2023, the Historical Archives–Museum of Hydra presented a retrospective of Angelika’s work, a journey through decades of etchings, watercolors, and flower canvases. For her, it was both recognition and renewal. “I can imagine another exhibition with my recent collages,” she says, “and I dream of including the music of my husband’s father, Dimitri Lialios, whose Mahler-influenced symphony was performed in Prague.”

These days Angelika still paints, and also teaches. Together with her daughters—actress-turned-yoga-teacher Skyrah and author Kai, who writes under the name Kai Knight—she has opened her Hydra home to visitors under the name Artemis Retreats.

“Some people haven’t drawn since childhood,” she says. “Then suddenly they create something amazing. We start simple—with sketches, then watercolor, then gouache. It’s about rediscovering play, the joy of making.”

The retreats now include creative writing and yoga, extending Hydra’s long tradition of cross-pollination between disciplines. For Angelika, it is less a new project than a continuation of the life she has always lived here: art woven into daily existence, shared with others.

Hydra, Still

Sitting in her centuries-old house, Angelika is surrounded by quiet beauty—beams darkened by time, carved furniture, stone floors worn smooth. She draws inspiration from everything: the patterns of embroidery, the calmness of the house, the way light falls on wood. “We keep it as it was—no TV, no noise,” she says. “That’s what people love when they come. It’s a way to escape.”

For Angelika, art has never been separate from living. It has carried her through love, family, change, and return, always finding new forms without abandoning its essence. To look at her work is to glimpse the constancy behind all reinvention: a devotion to beauty and to the act of creation itself. That, more than any myth of Hydra, is the creative continuum she embodies.