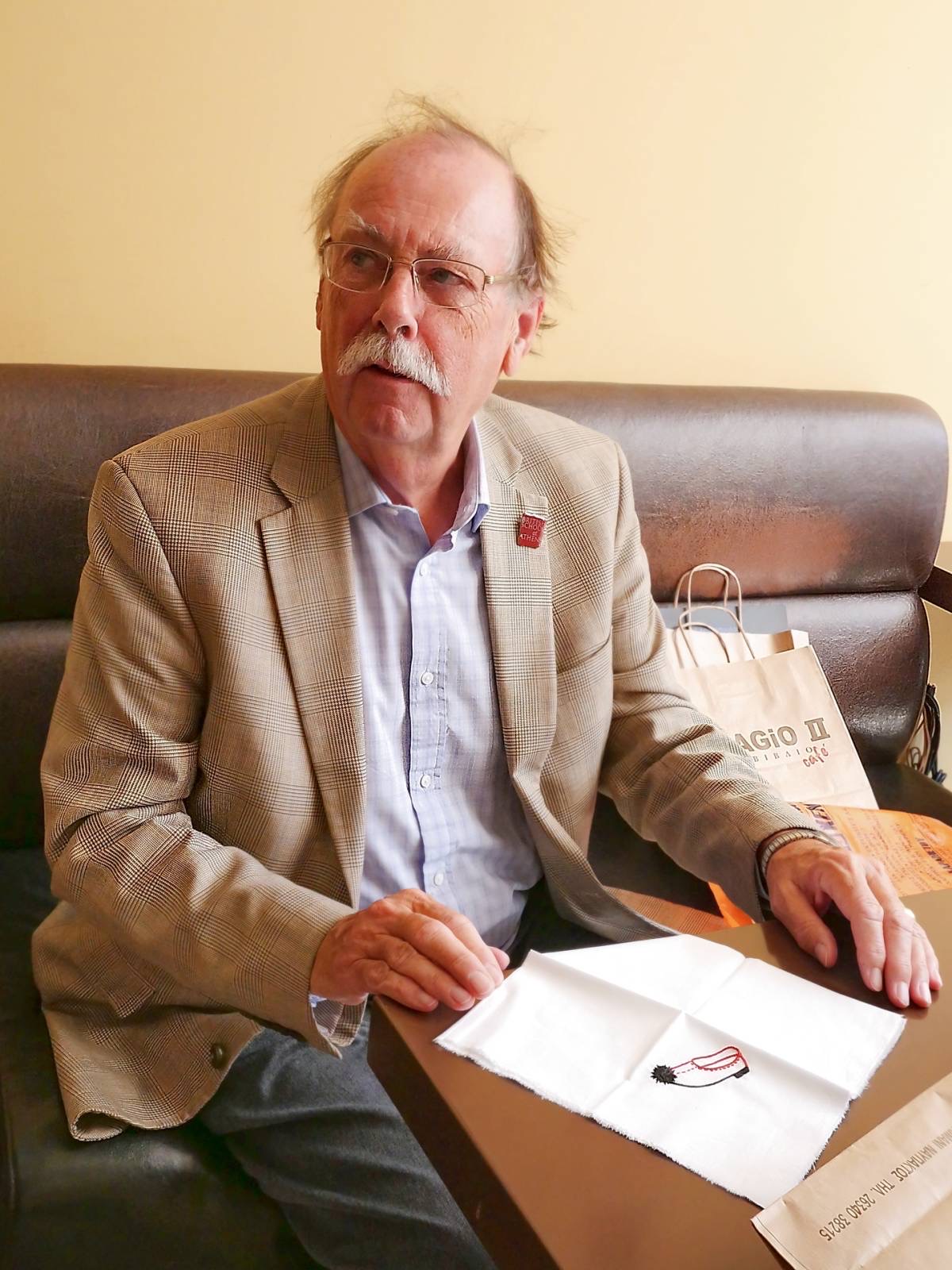

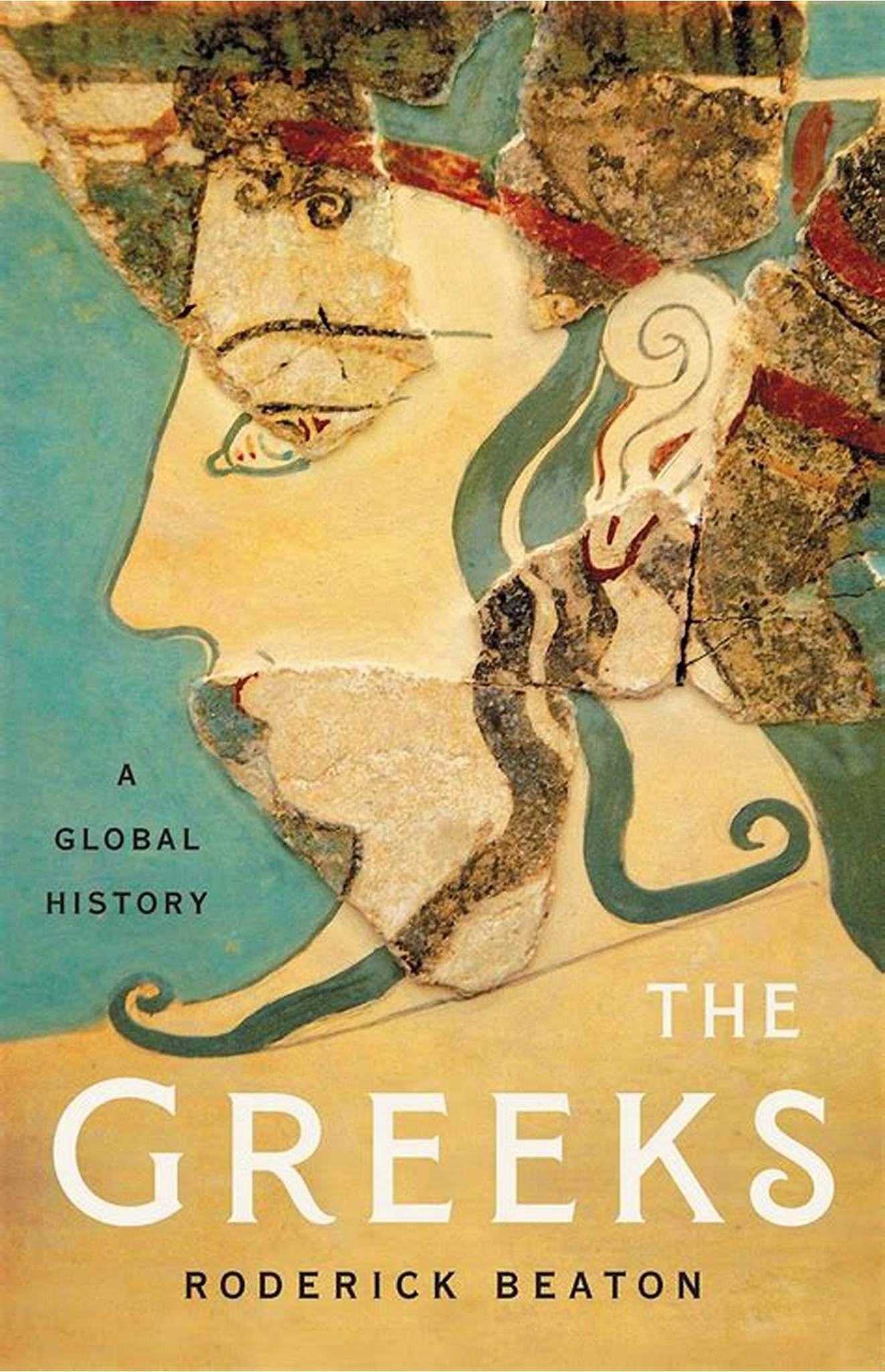

Roderick Beaton is an Englishman, yet more Greek than many of us. We met him in Nafpaktos after his presentation of his book “The Greeks – A Global History”. Beaton is an English retired academic and ever-active author who served as Professor of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language, and Literature at the “Koraes” Chair, at King’s College London from 1988 to 2018. As an author, he has penned books featuring characters from Lord Byron to George Seferis (including translations of his poetry). He loves the Greece of the Zagori villages, back when they still had Sarakatsani shepherds, and the five-day festivities of the Carnival in Karpathos.

I met him in Nafpaktos, where he arrived following an invitation from the Nafpaktian Brotherhood Society that organises various educational and cultural activities, relayed by the Brotherhood’s scientific advisors (Spyridoula Dimitriou, PhD in Art History, and Stavroula Polonyfi, conservator of antiquities, former employee of the Ephorate of Antiquities).

How did you feel receiving an honorary doctorate from the University of Patras, and after your book presentation at the emblematic Adagio II bookstore in Nafpaktos?

You can’t quite fathom the honour for a foreigner to be celebrated in such a manner by the University of Patras with an honorary doctorate. I was also deeply thrilled to present my book “The Greeks – A Global History” in Patras and Nafpaktos. We’re talking about three events that all gathered crowds and, despite being different types of ceremonies, shared a common thread of emotion – naturally, the nature of the emotion varied at each. Hearing gracious speeches from my younger colleagues and academics at the University of Patras, donning the official academic gown, and addressing the public was surreal.

I began by saying, who could’ve imagined that a 16-year-old kid who disembarked at the port of Patras, holidaying in Greece with his parents, would be honoured 50 years later, in the same city, in such a way. One of my first encounters with Greece was there, at the port of Patras, during the first year of the Junta in 1967. Back then, my grasp of politics was minimal, not what it is today. So, I experienced the holidays in Greece with enthusiasm for the place and its people, coinciding with the commencement of my Ancient Greek lessons at school in Great Britain.

That’s where the connection between the place and the ancient language began for me. Gradually, that path led me to Modern Greek Studies. The field that has now made me an honorary doctor at the University of Patras.

What was it that steered you towards Modern Greek Studies? Can you encapsulate it in a single image?

It was a balmy summer on the island of Mykonos, the kind of day where the breeze carries a hint of adventure. I stood on the dock, the Aegean wind in my face, awaiting the small boat that would ferry us to Delos. There, amidst the ruins, sat a forgotten jukebox—a relic from another era—its music arresting us all in sheer wonder. That melody, mingling with the sea and the chattering crowd on the dock, etched into my mind the raw beauty of the Modern Greek language.

Later, back in England, as we grappled with a segment of the Odyssey featuring Nausicaa—Homer can be a beast to decipher—it was that very image that came to my rescue. The language that seemed so obstinate on paper sprang to life, echoing the shouts of the sailors and fishermen back on the docks of Mykonos.

So, you wanted to seek out the living essence of the language?

Indeed. The experiences on the dock breathed life into Homer’s words, and in turn, Homer lent a profound depth to those memories.

What mistakes by the Greeks have led the international community to undervalue their modern history, celebrating only the ancient?

Treading carefully here, as a foreigner and someone honored by the Greeks, I’ll say this: Modern Greek history and literature have long been overshadowed by the ancients. Take the Greek War of Independence in 1821—it achieved what the ancient Greeks never did: a unified Greek state. And consider that the ancient Greek civilization crumbled after endless civil wars amongst city-states. Before the arrival of King Otto, there was the notion of a Greek Democracy, an idea hailing from antiquity, yet something the ancients could never quite manifest into reality.

Abroad, everyone raves about the Spartans, the Leonidas’ 300. Yet few know of Greece’s heroic triumph over Mussolini’s Italians or the brave resistance against the German Nazis that delayed their planned onslaught into Russia during World War II. In England, they whisper it, framed by context—the epic of Albania. Plaques outside Parliament speak volumes, but you’re spot on: any foreigner is more likely to have seen the movie about Leonidas’s 300 or played the video game.

And Byzantium has a history that has been overlooked by most and remains in the dark

It was probably overshadowed by the Orthodox Church. Because all that remains of Byzantium is the empire’s religion and the church.

Why would the church do that?

Consider that Byzantium was also a secular empire, dripping in wealth. Byzantines were warriors of renown, extending their reach in ways not dissimilar to Alexander’s empire. When Western Europe was ensnared in the so-called “Dark Ages,” Byzantium was basking in its zenith. The Franks deliberately played it down. Even in Greece, it’s not remembered as it should be—yet Byzantium is a chapter of Greek history that took a different shape in the Middle Ages.

Was the Great Schism of the Churches the trigger for “countless woes”?

Indeed, I believe the real catastrophe for Byzantium and Constantinople wasn’t in 1453 with Mehmed II, but in 1204 with the Fourth Crusade. The Catholic crusaders, along with the Venetians, ransacked the City. They essentially obliterated Byzantium. And unwittingly, they razed Europe’s mightiest bastion against Islam, Arab or Turk. The second fall of Constantinople was a dire consequence of the first.