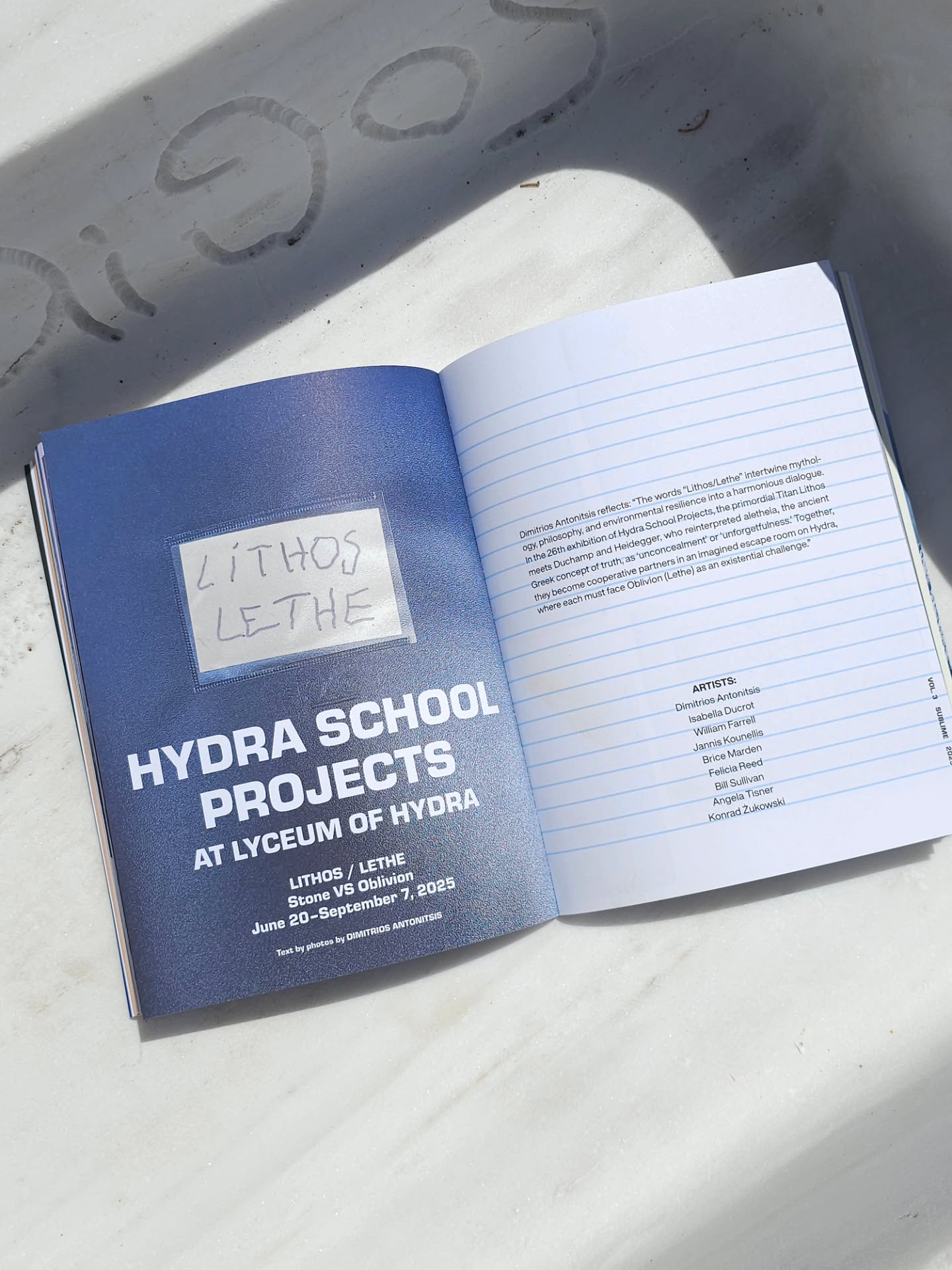

“I have a DNA which is very similar to the mules of the island,” says world-renowned artist-curator Dimitris Antonitsis, half-smiling, as he leads me through the classroom-turned-gallery of the Hydra School Projects’ 2025 exhibition, Lithos Lethe – Stone Versus Oblivion.

It’s a typically ‘Antonitsian’ metaphor: stoic, tongue-in-cheek, and pointed. For 26 years, he’s been ferrying art, ideas, and vision up Hydra’s steep mule tracks, building an annual project that defies categorization – part art exhibition, part thought-provoking platform, part spiritual offering to the island he loves.

The Vision Behind Hydra School Projects

Founded in 1999, Hydra School Projects (HSP) began as a deeply personal gesture. “I wanted an excuse to spend as much time as possible in Hydra,” Antonitsis tells me. “Back then, there was a huge Bohemian community on the island. Very eccentric people. And I thought this would be a wonderful way to give something back to the island, to the community.”

The first official show launched in 2000 and never stopped – not during the Greek economic crisis (click here to listen to our radio interview on Athens International Radio at that time), not during COVID. “Every year, even during the crisis, even during the pandemic – we kept going,” he says. And while much has changed, the project remains fiercely non-commercial and guided entirely by Antonitsis’ personal themes and curatorial outlook.

“Every show is a thematic show, always something that concerned me as an artist,” he explains. “In the ’90s, it was about gender and identity. Then it shifted to objecthood. Then to culture. Each title is like a small biography. It’s a kind of treasure map.”

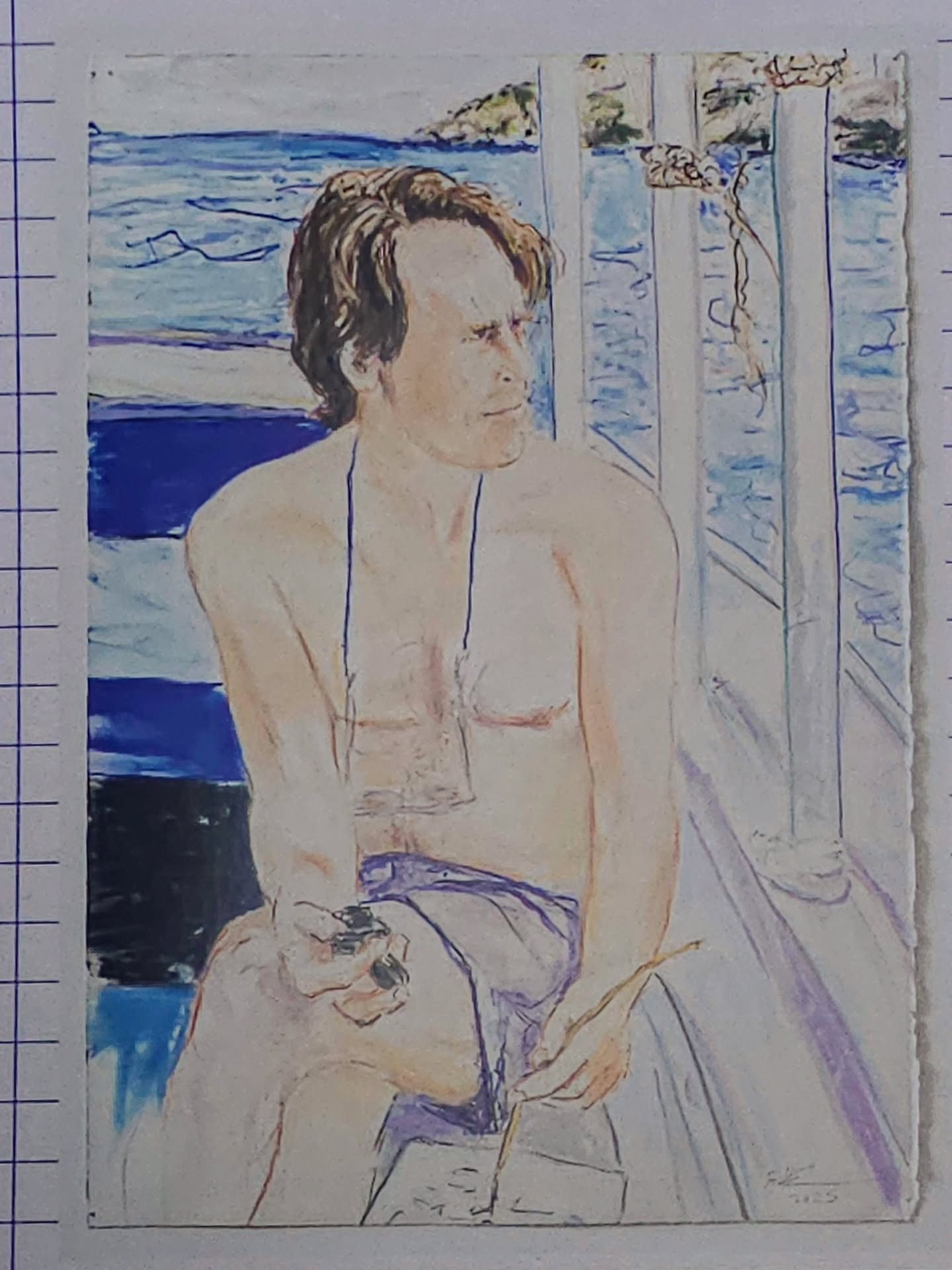

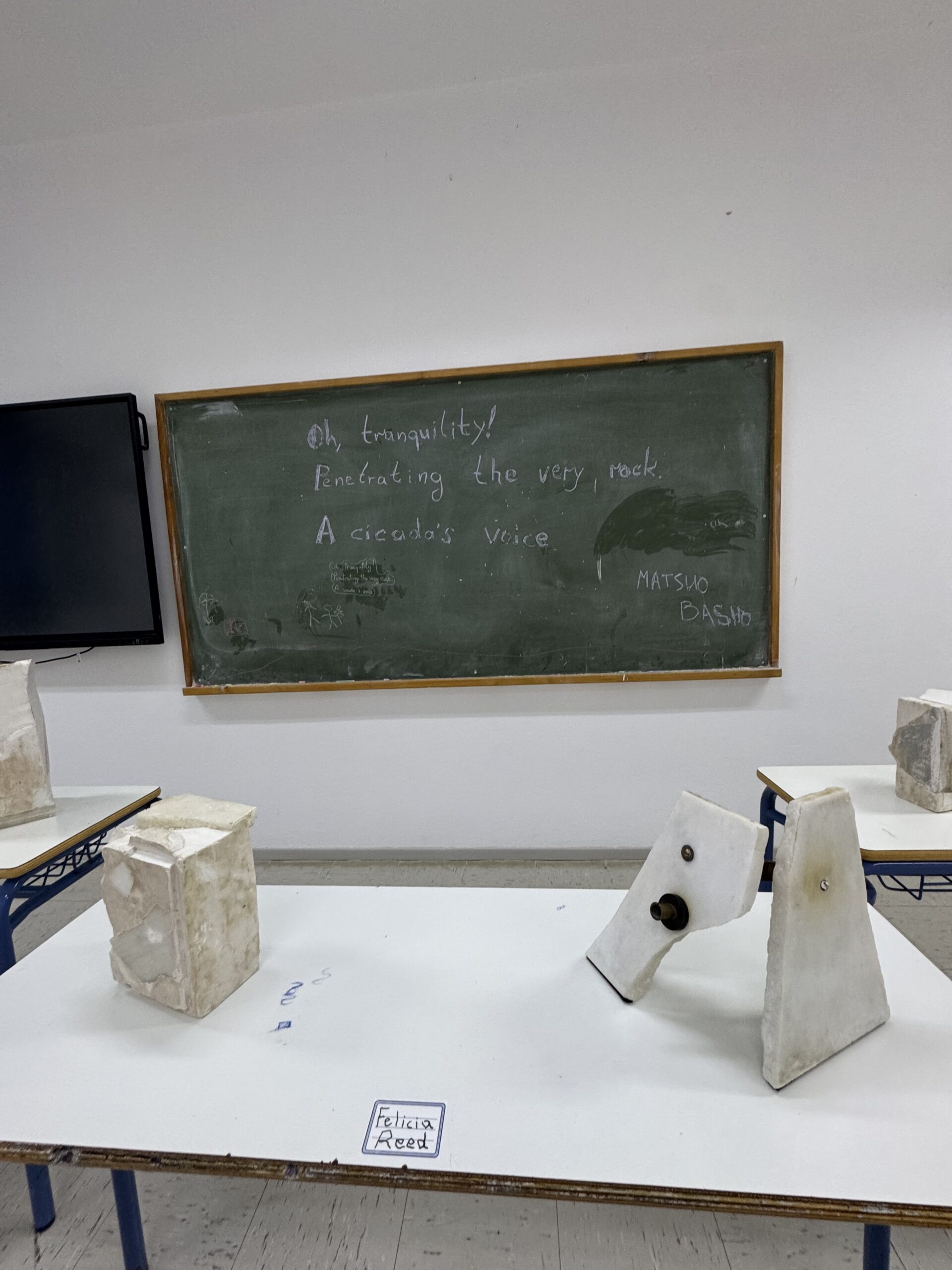

The result? Over 300 artists have shown here—some major names, others exhibiting for the very first time in Greece. This year alone features 93-year-old Isabella Ducrot from Rome and mid-30s Felicia Reed, who moved to Athens from the US. In another classroom, Konrad Żukowski and William Farrell, young artists, are presented alongside the works of contemporary pastel master Billy Sullivan from NY.

“I love mixing young artists with older artists and doing these summer cocktails,” Antonitsis says with a twinkle.

Curating Dialogues, Sculpting Truths

Lithos Lethe, unfolds across classrooms in the Lyceum of Hydra. This year’s exhibition, Antonitsis explains, is “totally dedicated to the island.” The title, drawn from Greek, contrasts “stone” – something ancient that holds a great deal of memory – with “oblivion,” – the human and natural essence and sometimes need for forgetting one’s bearings. It suggests a meditation on permanence, remembrance, and perhaps even, as much of our society tends to do today, swinging between a state deeply set in the constructs of ‘reality’ yet completely detached from it at once.

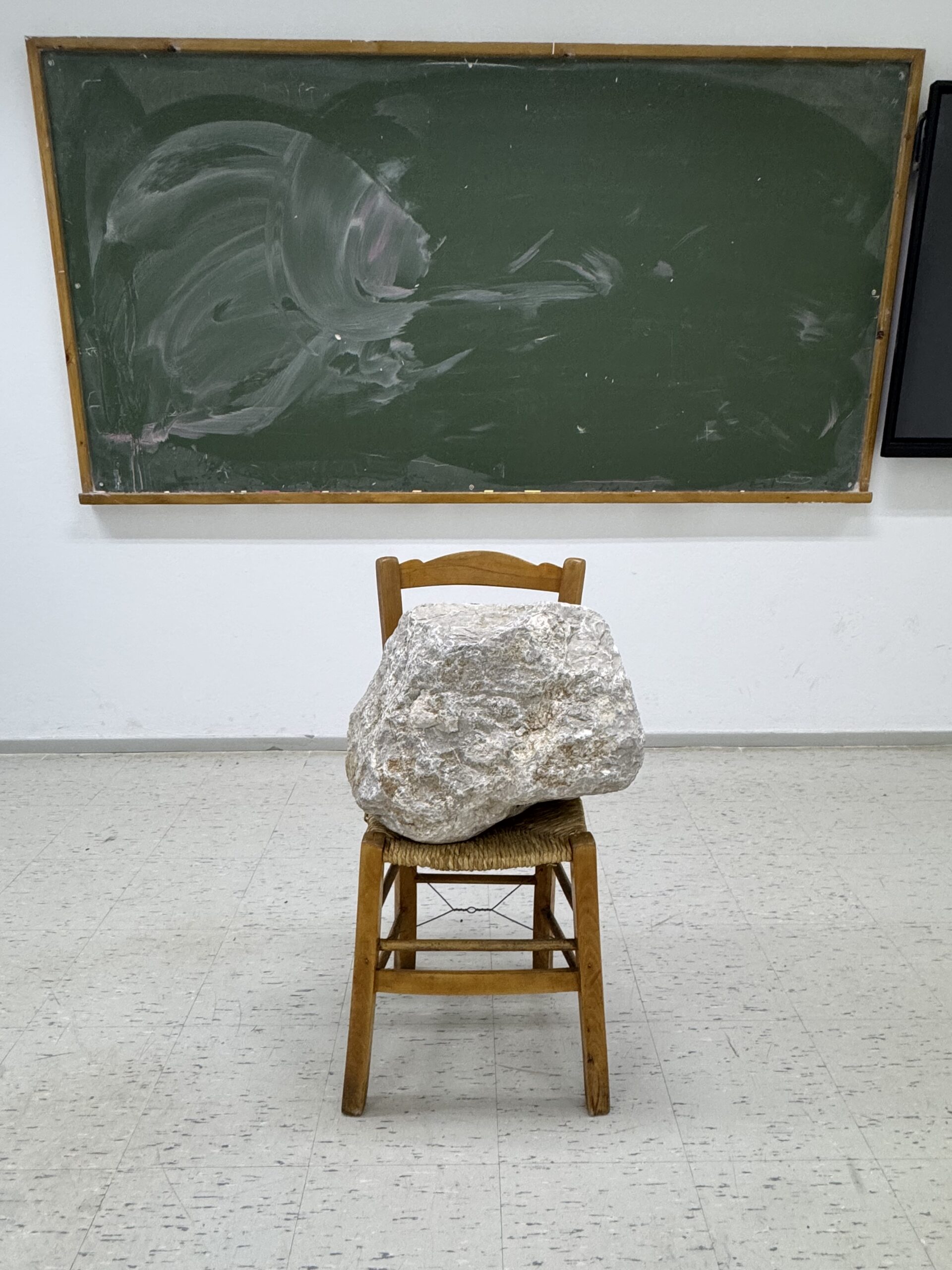

In one room, a quiet but charged pairing brings together works by two titans: Brice Marden and Jannis Kounellis. Though both had studios on Hydra, the two artists never connected – but here, their works are in profound visual dialogue, both aesthetically and energetically. “This very piece here by Brice gave me the idea,” he says, pointing to a marble slab with handwritten notations. “It reminded me of Kounellis’ canvases with writing from the ’60s. That was the portal. The bridge.”

Antonitsis curated the pairing himself. “These are museum pieces,” he adds, almost reverently. “The last three marbles Brice did in his career. And Kounellis’ ‘Rock Upon the Chair’ – is also a museum piece. This is a serene classroom. For me, it’s my meditation chamber. I come here every day.”

The Artist-Curator

Antonitsis is no ordinary curator. He’s a practicing artist with a singular trajectory. He was born in Athens in 1966, educated in Mechanical Engineering at ETH Zurich and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, and trained in high-speed microscopic photography. His early experiments in film earned recognition – including a collaboration with Robert De Niro’s studio. But it is sculpture that now anchors his practice.

“The past 15 years, it’s been sculpture for me. Very labor-intensive work,” he says. “Earlier it was photography and film. But I find photography closer to sculpture than to painting. I feel it’s about how you understand volume and light.”

His sculptural language moves between attractive minimalism and exaggerated folkloric detail, often addressing themes of luxury, power, and mundanity. But here on Hydra, he also becomes a weaver of curatorial constellations – a role that feeds back into his studio life.

“It’s exhilarating,” he says. “I step out of my studio and see how other artists solve the same subject matter problems. Contemporary art is vast. So much imagination. That’s why I keep doing it.”

Hydra: The Chosen Island

Though his work and the works he chooses to curate could easily belong to international art fairs or glitzy galleries, Antonitsis remains devoted to this singular Greek island. When I ask him how he thinks the Hydra School Projects may have shaped the island’s art scene over 26 years, he humbly responds: “I used to sail, and always Hydra gave me the most memorable memories.”

Would he consider exporting this curatorial model elsewhere? “No,” he answers without hesitation. “Even if at some point I stop doing the shows, I won’t stop coming to Hydra.”

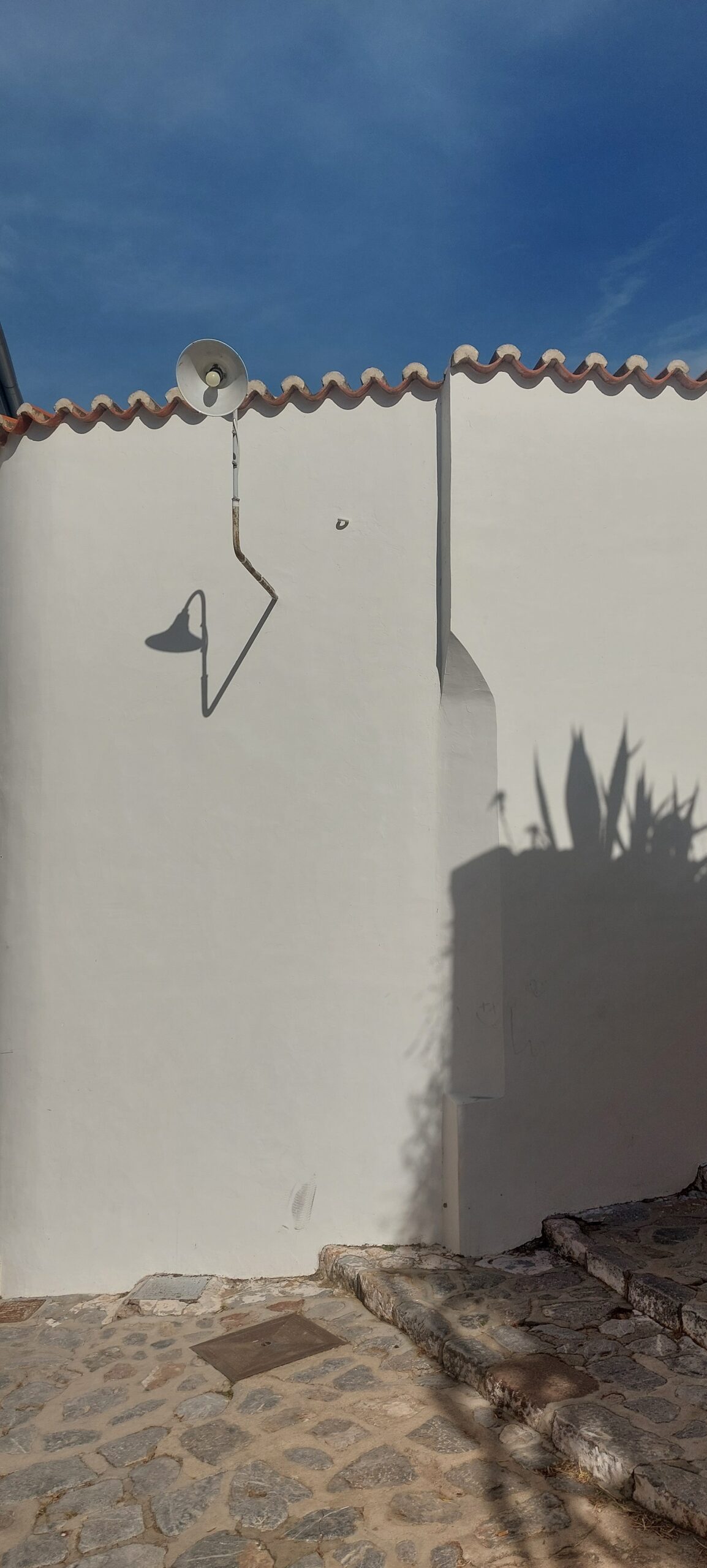

Whether he admits it or not, the annual exhibition has however, transformed the island in subtle, slow-burning ways – not through tourist campaigns or commercial hype, but by making contemporary art accessible to the general public in a non-elitist way in classrooms and old schools, often with no entry fee and no fanfare, while at the same time bringing over true art aficionados (and pretend ones too) who want to see, connect and somehow be part of what he creates.

“Kids can come in and check out what I did in their classrooms,” he says. “Some of these pieces are insured for millions. But it’s not about money. It’s about exposure, education. That’s why it’s called Hydra School Projects.”

Against the Scroll

There’s a note of resistance in everything Antonitsis does – not loud rebellion, but quiet, stubborn refusal to simply follow the crowd. That extends to his relationship with the internet and social media.

“I’m not a big online fan, as you know. I have no social media presence,” he says. A collaborator convinced him only this summer to create a Hydra School Projects Instagram account for the show, but even that feels invasive. I ask whether it hurts. “It hurts a lot, yes. It’s another little sign on the screen of my mobile.”

Why the resistance? “I want real, personal contact. I thrive upon it. I’m not good with just emojis. I want the flow of energy that comes from in-person interaction.” It’s not a fear of distraction. “In communication, you have to see who’s in front of you. Old school. That’s the way it is.”

Memory, Oblivion, and the Sink from Knossos

In another room of the exhibition, Antonitsis points out one of his own works – a sink sculpted from pink marble – so pink I was convinced it had been painted by the same artisans who love to decorate Greek houses with those ‘taramosalata’ hues – sourced from the same quarry that supplied the Palace of Knossos 3,000 years ago. The sink represents an everyday object – something we all have in our homes, where we wash things away, where we watch dirt spiralling down the drain, never to be seen again.

“It’s titled ‘Aletheia’, which means truth — the opposite of ‘Lethe’,” Antonitsis says. “In ancient Greece, not to forget was an apocalyptic reality. Because remembering was truth. Oblivion, forgetting, was part of being human.”

He references Plato’s myth of the soul drinking from the waters of forgetfulness, of stone as a vessel of memory, of functional objects as philosophical triggers. “The truth of stone,” he calls it. “We are designed to forget. But the material remembers.”

A Legacy Carved in Time

Over two and a half decades, Hydra School Projects has become more than an art platform. It is, in a way, a self-portrait in evolution – of the artist, the island, and the age. “It made my summers meaningful,” he says. “It gave me a different torque from where I was going.”

And where is he going now? “Every year, I just hope I’ll be able to secure funding for the next curatorial. Sponsorship in Greece is unpredictable. But if I can keep going – I will.”

We step into the white-hot Hydra sun and cross to the school’s pocket amphitheater, where Antonitsis’ marble blocks flare like beacons, their etched words catching every shard of light. Around us the island vibrates – memory in the stones, presence in the air, a low, timeless hum that refuses to fade.