A little before 7am, I lowered my feet onto the thick, warm rug by my bed. Some light from the village of Agios Athanasios crept through the window diagonally to form a shadow of the wooden veranda onto the room ceiling.

The windows were still foggy with condensation, heavy drops of dew running down slowly as a reminder of the contrast in temperatures inside and outside. I opened the door shutters purposefully, despite the cold, as my day slowly got underway. At this hour, the sky was just beginning to turn blue; it was cloudy but not raining and the scent of the moist earth filled my lungs.

From the second floor of the Titagion hotel, where I had spent the night following a long drive covering countless kilometres across northern Greece ahead of my trip’s eventual drive south back to Athens, the eastern side of the Tavropos lake, or Plastiras, as the lake is commonly known, faded into the hazy autumn horizon.

The route around Lake Plastiras, approximately 50 km long, is a winding course offering dense nature, traditional villages and houses, elegant guesthouses, tantalisingly delicious food whose recipes are rooted in the region at local tavernas and restaurants, as well as places ideal for recreational activities and the exploration of nature.

The manmade Tavropos (Megdovas) Lake, or Lake Plastiras as it is commoly known, takes its name from Nikolaos Plastiras, a general and politician who envisioned the project that ended with the completion of a dam at Kakavakia in 1959.

The valley region that was filled with 400 million cubic metres of water by the Tavropos river, flowing to intersect with the Achelous river, was known as Nevropolis, possibly as a result of the many deer that formerly lived in the region; Nevros means fawn. Around 1928, general Plastiras came up with the idea for the construction of a dam that would provide a solution to the Thessalian plain’s irrigation problem, ensure water supply to Karditsa and other communities, and also generate hydropower electricity. The idea did not come to fruition for another 30 years but once developed, the manmade lake added a unique beauty to the area, putting it on the tourism map in more recent decades.

I was driving slowly at no more than 30 km/h as I had decided to absorb every single kilometre of the 50-km distance around the lake. On weekdays, the traffic flow around the lake is minimal and autumn’s orange and brown coloured nature surrounding the lake seemed wonderfully mysterious and otherworldly, like a painting evoking both melancholy and optimism. The villages I drove by, Kastania and Mouha, broke the overall setting’s colourful homogeneity as they sat quietly by the edge of the lake. The smoke billowing from the chimneys of village houses offered signs of life in the area.

Sheep occasionally roamed parts of the road around the lake, the sound of chainsaws was audible as locals cut their firewood, stylish guesthouses adorned the route, while the scent from kitchens, both professional and domestic, offered intangible proof of cooking in progress. To my right, numerous clearings between trees unveiled fresh views of the lake. As time went by, the shifting clouds, lying low and touching the surrounding peaks, began to spread and give way to an all-blue sky and bright sun. Brown cows looking as if they had adopted the dominant colour of the autumn season, like November chameleons, walked carefree in the middle of the road, oblivious to any passers-by. All seemed perfect, except for potholes, small and bigger, covered by piles of fallen leaves and waiting like camouflaged landmines as a challenge for the tyres and suspension system.

The tourist shops by the dam were closed the day I was there. The silence was almost deafening; the project, of French design, looked incongruent amid the overall setting, resembling a futuristic image from the past. A large signpost at one end of the dam offers a rundown of the project’s history, and the view of the entire construction from across the other side, as the road leads away and heads uphill towards Neohori is incredible.

Neohori, the region’s main village, west of the lake, is like a borderland signalling change. This is the point where the vegetation begins to transform, thinning out from dense to scattered with fields, clearings and, at lower altitudes, a variety of access routes to the lake. It also has the greatest number of accommodation and dining options anywhere around the lake area. Neohori has grocery stores, a pharmacy as well as the Artemis café-bar, where, besides cosy hospitality, drinks and snacks, customers may be extensively educated on mushrooms by proprietor Giorgos Karantonis. A short fireside chat made clear his passion for mushrooms and offered an incentive for an exploration of the local hills.

Leaving Neohori in a northerly direction and taking a right turn towards the lake, a signpost to the left informs of your arrival at the Neohori botanical garden. This well-kept space emerges as a pleasant surprise. It is run by botanist Giorgos Karantonis, who, coincidentally, shares the same name as the owner of the aforementioned Artemis café-bar.

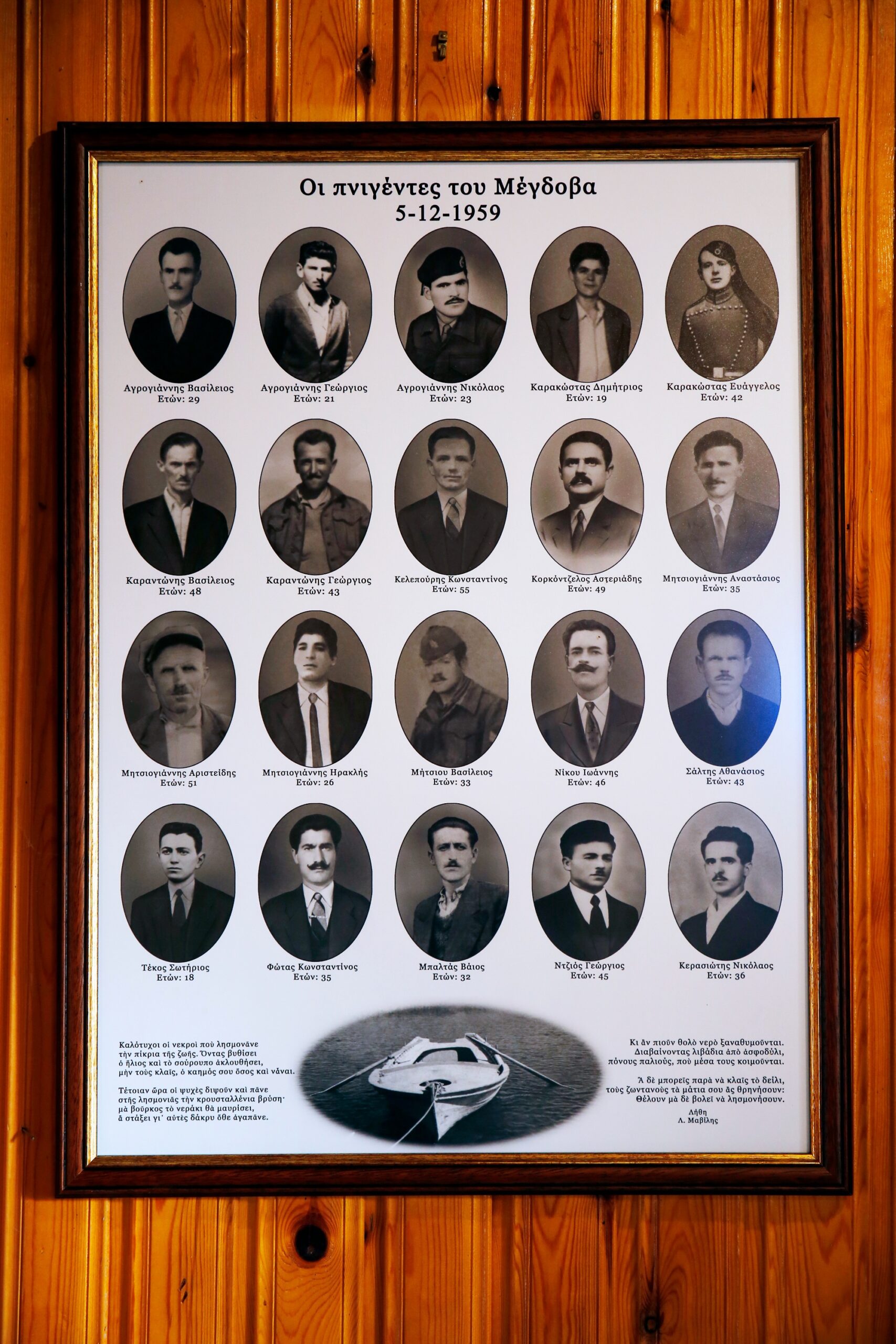

The botanical garden hosts a large range of local flora, entire small-scale ecosystems, as well as various plants, shrubs and trees from other parts of the world that have thrived in the lake area’s microclimate. The garden is open throughout the year, welcoming school and group excursions, while its delightful wooden cottage hosts a photography exhibition offering insight into the history of the lake as well pictures covering a tragic incident in December, 1959, when 20 people drowned after the boat they were on capsized.

As I stood at the edge of the lake, at Pezoula beach, gazing into the lake’s horizon, I tried to imagine how cold the waters would have been for the victims on that tragic day.

These anxious thoughts were erased by my meeting with Electra and Alexandros, who co-run Tavropos Activities, offering mountain biking, paddle boating, canoeing, and archery at Pezoula beach.

I had worked up an appetite after a day’s worth of activities, photography, chatting and driving, so, a little before dusk and on my drive back to Athens along the brand new E65 highway, I stopped at Tsardaki, a beloved small taverna in Moschatou, Karditsa, for a much-anticipated visit. A family venture, it is now into its third generation.

Chickpeas with eggplant, baked in a wood-fired oven, were brought to the table along with some homemade pickles, goat’s milk cheese, a generously sized piece of Plastos – a local corn flour pie with greens – and, unfortunately, because of the drive ahead, just one glass of red wine. It all amounted to paradise.

As I prepared to leave into the night, taking with me assorted delicacies packed for me by the taverna’s proprietor, Stavroula Korobilia, along with two rooster-shaped red lollipops, a shop trademark gift usually saved for youngsters, I had already come to the obvious conclusion of promising myself to return to Lake Plastiras, but next time not just for one day.

Read also:

4 Greek villages next to stunning lakes

Greece’s Lake Ziros: A Hidden Gem ideal for Canoeing and Hiking