The peaks of the Pindus Mountains tower above you and the cobalt blue waters of the Megdovas River rush below your feet as you clatter across the old Bailey bridge in the middle of nowhere.

Climbing the road out of the river valley, you feel like a lone explorer as the emptiness envelops you: the villages are few and far between and the winding road is empty. There are occasional signs of life here and there, but no people.

Instead, the majesty of the mountains encircles you in their embrace: their snowcapped peaks weathered and ragged, their slopes scarred by rockslides. Waterfalls and gushing springs spurt from the earth and nature’s beauty is everywhere. Birds of prey dot the skies and, if you are lucky, you will see a wild deer or a wild boar dash across the road in front of you.

This is the Agrafa. The name literally means the Unwritten, as in uncharted and untamed. Here time stands still and the wilderness encroaches on the world of man. The name itself captures the secret and enigmatic atmosphere of the place.

The reason for the unusual name is lost to history. Some say tax collectors in Ottoman times feared to tread here and struck the villages from imperial tax rolls. Others think the iconoclast Byzantine Emperor Constantine V erased the region from imperial maps for its refusal to destroy Christian icons. A third opinion holds that the name comes from the somewhat mysterious Agraei tribe of ancient times.

No one really knows, but what is certain is that, from antiquity up until today, the Agrafa has always been way off the beaten path. A place to get lost – and to lose yourself.

It is a land of many mountains and very few people. The Agrafa is one of the most mountainous parts of Greece – a place of Alpine meadows and narrow, rocky gorges – with seven of its peaks above 2,000 meters (6,500 feet) in height. The population of just a few thousand is spread out in roughly 150 villages across an area straddling the provinces of Evrytania and Thessaly, from Lake Kremaston in the southwest to Lake Plastiras in the northeast. And with a total population of only a few thousand, it is also one of the 10 least densely populated regions of Europe with just seven permanent residents per square kilometer.

Ghosts of History

On this trip, my destination is the village of my ancestors, Granitsa, a name I carry with me. The first time I visited the village, almost 50 years ago, I was a child and it felt like a great adventure.

Back then, the trip from Athens took two days. We traveled in a crowded VW van with others returning for the village panagyri (festival) on August 15. The road from Karpenissi was very rough, and every so often we would stop to fill potholes in the road for the van to pass. There was no AC and clouds of dust blew through the windows.

Where Community Gathers

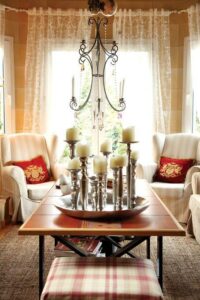

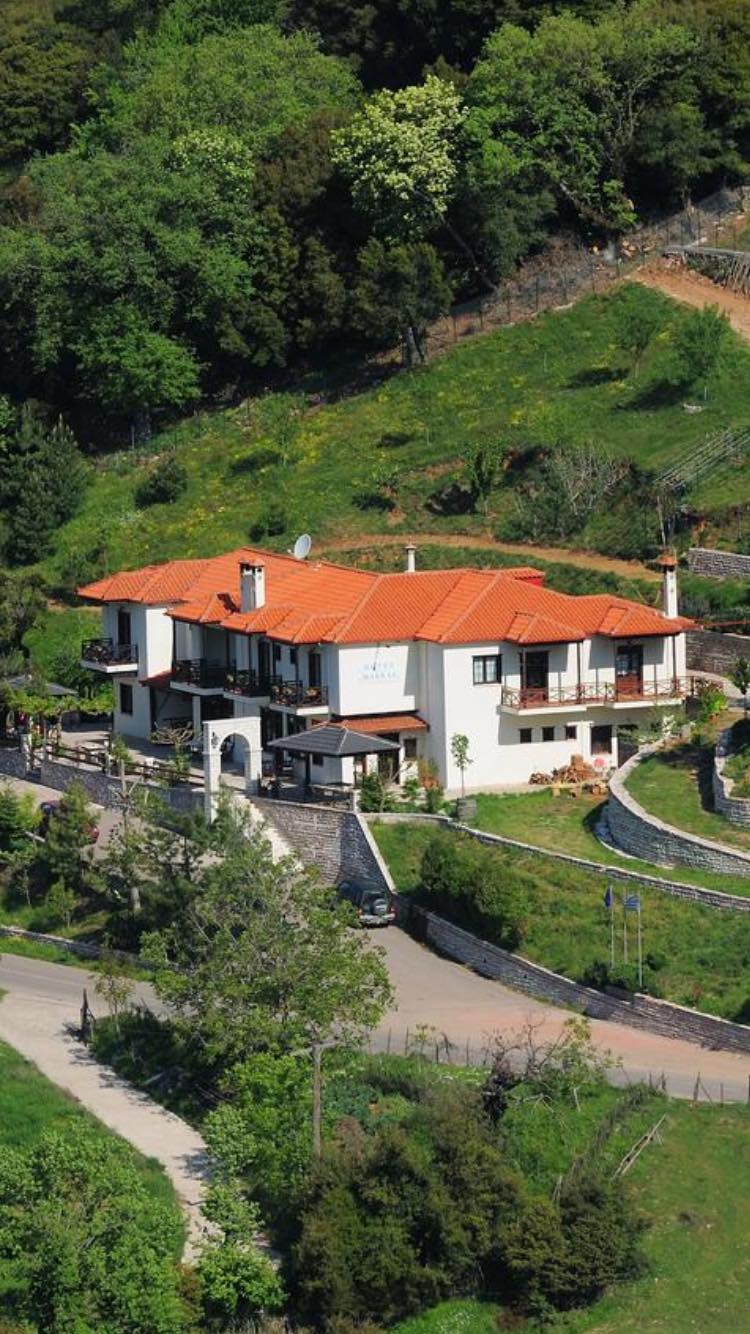

My first stop on this visit is the neighboring villages of Kerasochori and Krentis. In the emptiness of the Agrafa, the Hotel Makkas in Krentis – one of the few hotels in the region – is a warm and inviting oasis.

The downstairs lounge with its cozy fireplace is where the residents of the two villages gather. On one evening, the older men come to play cards. On the next, a gaggle of teenagers fill the place with lively chatter. In between, owner and native son George Makkas, a warm and hospitable host, tells you about the Agrafa of his childhood: when there was no electricity or paved roads and trade was in kind rather than cash. Always happy to chat, George is a good reminder that the way to discover the Agrafa is through its people.

Nearby Kerasochori has only about 70 residents, while somewhat larger Krentis offers two tavernas and a café. But the real attraction in the area is the abandoned village of old Viniani, just a 20-minute drive away.

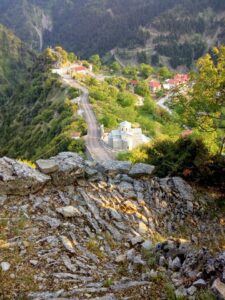

Viniani is perched on a steep hillside, surrounded by mountains and with the Megdovas River winding through the narrow valley below. Here, during the Nazi Occupation, Greece’s four major resistance groups banded together in March 1944 to form the Mountain Government. The schoolhouse, where they met, is now a small museum that makes you reflect on Greece’s recent history, and the refuge these remote mountains offer.

Just below the school is the ghost town of Viniani. Abandoned after a devastating earthquake in 1966 – and now with just three residents – the village has an eerie, but dignified presence. Stately homes and small mansions grace the hillsides, a testament to the village’s former prosperity. And in the distance: the old, 17th Century stone bridge across the river, about three kilometers away.

Ascending the Agrafiotis River Valley

In the five decades that I have been coming to the Agrafa, much has changed. The bone-crunching dirt road I remember from my youth was paved a long time ago. But even so, in the upper reaches of the central Agrafiotis River Valley, dirt roads still abound and are sometimes impassable because of either snow, flooding or rockslides.

From Krentis, I am heading up the valley to the Stanas Monastery and then on to the town of Vraggiana, once an important center for theological studies during Ottoman times. First, though, I must get gas. The only way to visit the Agrafa is by car or motorcycle, but there are only four gas stations within a 50-kilometer radius and one of them is here in Krentis.

About 15 kilometers into the valley, an impossible concrete road scales the steep slope to the right, leading to the Stanas Monastery, glued to the rock face hundreds of meters up. After a nerve-wracking ascent to reach the monastery, you are rewarded with an astonishing view. From here you see only sky, mountains and the rushing river below.

It feels like the ends of the earth, much like it must have felt a thousand years ago, when legend has it that a sacred icon of the Virgin Mary was found in the rockface. But the real wonder is the monastery’s exquisite iconostasis of richly decorated wooden panels, painted with intricate patterns in brilliant colors, adorned with gold accents.

To see it, you’ll need to find Father Galaktion, who lives in a small house below, sent from Mt. Athos three years ago to help restore the monastery. He’s quick with a smile and will happily engage you in a wide-ranging discussion about faith, love and the world’s religions, peppering the conversation with observations about Buddhism, Islam, and things he’s read on the internet.

Into the Wild

Back down in the river valley, I leave the asphalt behind and enter a narrow cleft in the rocks. The dirt road passes through a tight gorge that feels like a portal to a different world, allowing you to reach the upper levels of the Agrafiotis. Ahead lie the Alpine meadows around Vraggiana and the fir-clad hillsides around Trovato.

The valley here is one of the wildest and most pristine parts of the Agrafa. The last time I came through, I saw a mother deer, accompanied by three young, and a giant Eurasian eagle-owl. The 10,000 kilometer-long E4 European long distance path – which stretches from Cyprus to Spain – also passes up the valley, one of the prettiest sections of the trail in Greece. The scene of snow-capped peaks, high mountain meadows and forested hillsides quite literally takes your breath away.

Agrafa Village Life

The next stop is the village of Agrafa itself, the heart and namesake of the region. The village spreads elegantly across a high meadow with a majestic stone church perched on a rise. Climb the bell tower for a commanding view of the surrounding peaks and the big sky above.

Though the village has suffered the ravages of natural disasters and was burned to the ground by Italian Occupation forces in 1942, it still carries a certain grace. Here you can stop for a coffee, spend the night at Kyra Niki’s or Pyrgos Agrafon, and grab a meal at the nearby Neromylos (watermill) taverna.

You reach the village through a narrow ravine, and past the 17th Century stone bridge that vaults over the canyon. In the Pindus Mountains, these arched bridges, mostly dating from the 16th and 17th Centuries, represented vital infrastructure for their time and helped the region prosper. The bridges connected the mountain villages to the outside world and trade in handicrafts, produce and services blossomed.

In contrast with the Agrafiotis valley, the western part of the Agrafa is milder, more open. The land slopes down from the 2,000-meter-high summits to cradle the broad Acheloos River Valley and the emerald green Lake Kremaston. Facing west, the region enjoys the long, afternoon sun which glints off the surface of the lake, creating a dreamscape of light and shadow.

Perched close to the summit of Mount Liakoura, at the end of a long, and somewhat rough dirt road from the town of Palaiokatouna, lies the one-time hideout of pre-revolutionary war hero Antonis Katsantonis. From the cave here, there is nothing but sky, mountains, and a breathtaking view. Up here, you will see deer and wild boar, and an occasional sheep dog. The only sound you hear is the shrieks of the bird of prey and the rustling of the whispering trees.

The western slopes of the mountains also boast one of the Agrafa’s most striking geological features: the dry Bouzounikou river canyon located near the town of Valaorou. The gorge once formed part of the riverbed for the nearby Granitsiotis River. But in 1910, a catastrophic landslide, after heavy rains, pushed tonnes of rock into the river. The resulting flood was so violent that it displaced the river several hundred meters to the east, where it flows today, and left the Bouzounikou Gorge high and dry.

The gorge, mostly sheltered from direct sun, enjoys its own microclimate – an unusually lush and green ecosystem with a wide range of plant species. The place has a magical feel to it – you can almost imagine a mythical creature hiding around the next bend. Its 650 meters are an easy walk, suitable for all ages and well worth a visit.

Culture and Evolution

Several years ago, the Agrafa Mountaineering Association, founded by mountain man Thomas Davarinos, cleared the path and set up rock climbing routes along the side. More than 100 routes are now marked out on the canyon walls and featured during the annual rock-climbing festival hosted by the association.

Clinging to the western flank of the mountains is the town of Voulpi, home to the recently formed – and multi-award-winning – Agrafa Beekeeping Collective led by the highly energetic Katerina Geronikou. The delicious fir-tree honey is collected from an altitude above 1,000 meters and the collective offers, apart from honey, rakomelo, pasteli, natural candles and other products.

A little further along the road is my ancestral village of Granitsa. With its southwest orientation, the village is said to have the best view in the Agrafa and is described by some as the cultural capital of the region – birthplace of several famed authors, painters and singers, and the site of a local folklore museum.

And by the standards of the Agrafa, it is a bustling village of some 150 residents with two cafes – To Elato and Thelkxis, two tavernas – Agnanteue and Christina’s. It even has a hotel, the Panorama art hotel, a pharmacy and a nearby gas station. Each year, on the last weekend in October, hundreds of visitors descend on the village for the annual tsipouro festival.

This is the place I call home.