In the quaint village of Ano Karpathos, nestled at the southern tip of the Aegean Sea, the Byzantine Olympos community continues to uphold cherished traditions. Wisps of smoke emanating from their traditional ovens signify the baking of local “frouana” bread, a testament to their enduring heritage. These ovens and windmills stand as monuments to a simpler way of life, one that has faded into distant memory for many, making them valuable relics in our increasingly complex world.

The arduous process of bread-making in Olympos highlights the resilience of traditional communities as they navigate the challenges of their harsh surroundings. Towering mountains frame the village, a constant reminder that life is difficult but also deeply rewarding, as Papa-Yannis, the priest of the village, observes. Through overcoming adversity, the villagers find purpose and joy.

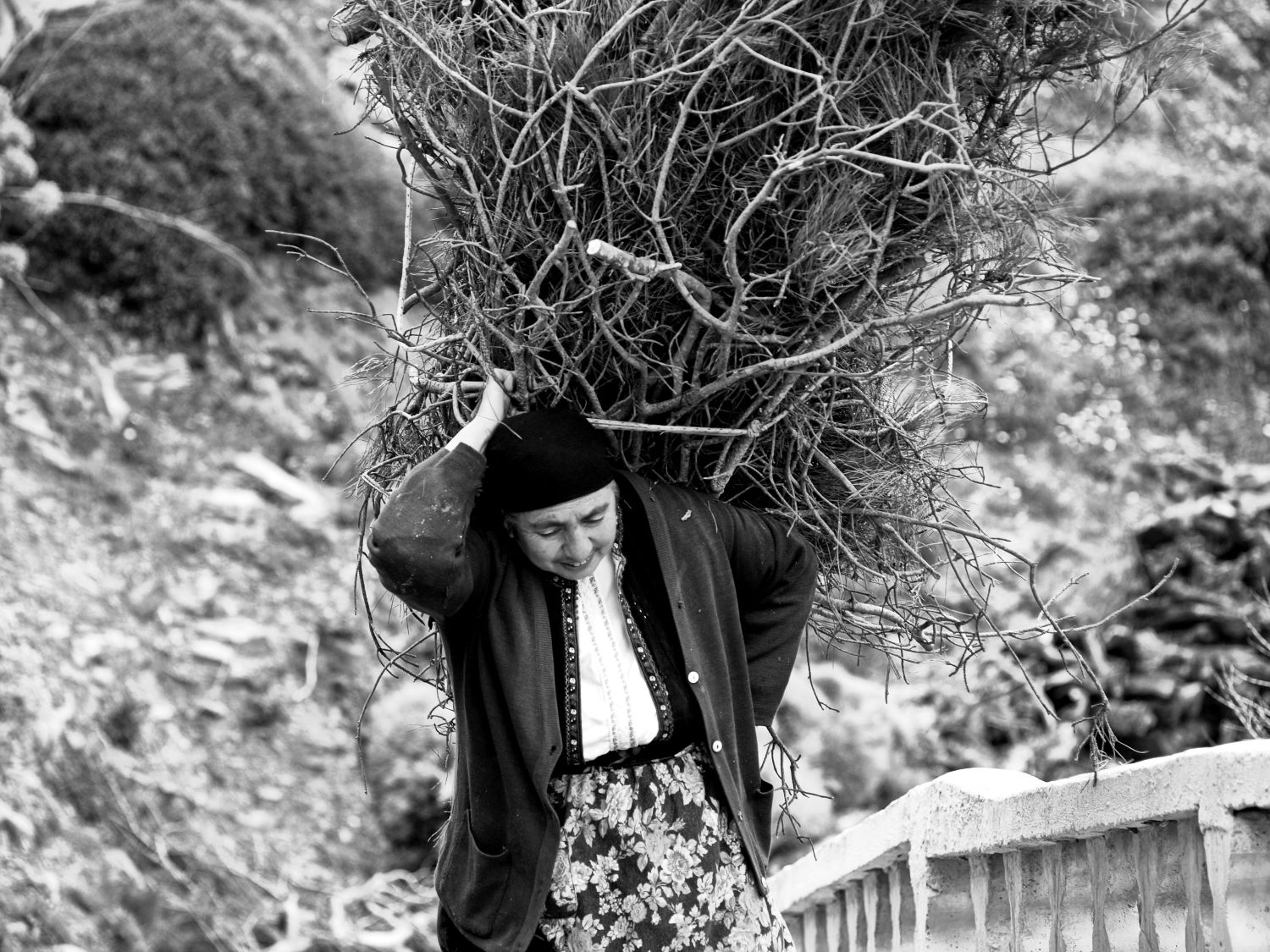

In contrast to the modern convenience of European bakeries, Olympos families take matters into their own hands, quite literally. Each week, they knead, gather branches, and bake bread in communal ovens, relying on a collaborative effort from start to finish. From ploughing, sowing, and reaping to threshing, milling, and collecting firewood, everyone plays a role in the process. Kalliopi, carrying a bundle of fragrant “frouana” pine branches on her head, bears a significant responsibility in preserving this way of life, as only a handful of people now share in these traditions.

Dressed in her traditional attire, which she has worn since she was a little girl and never replaces with modern-day clothes—even when leaving Olympos to visit Rhodes, Piraeus, Athens, or New York—Kalliopi rolls up her embroidered sleeves to begin the multiple kneading sessions for the Great Baking Holy Week in Olympos. Before everything, though, on the afternoon of “Red Thursday,” as Kalliopi refers to Maundy Thursday, she, her daughter Maria, and her two granddaughters, Despina and Kalliopi, gather at her house in the Troulinos neighborhood to dye sixty “argadia” eggs.

For the young girls, this is just the beginning of their initiation into the mysteries of Olympos’ Holy Week, just as it happened years ago for their mother and their grandmother. Maria and the young girls may now wear their modern clothes, but in the evening, at the service of the Twelve Gospels in the stunning Church of the Dormition, the mother will wear the somber black traditional costume of married women, while her daughters will don the flamboyant dress of unmarried girls and their precious golden jewelry.

The vibrant colors of Olympos’ attire extend to the traditionally decorated living room, adorned with woven textiles. Here, Maria shapes bread rings on the central table, while Kalliopi and young initiate Despina braid “poulos“—the traditional Easter bread with brightly colored eggs. “Come, my Christ,” says Kalliopi as she begins shaping the “ploumia” with one long and one thin strand of dough. She wraps them around a red egg, remarking with playful self-mockery: “the fool favors red.”

A red egg is also used for the “pregnant” figure, a human-shaped bread that cradles the egg in its hands on its belly. The eyes and nose are fashioned with cloves, and the fingers are meticulously crafted with a small knife. Despina follows suit, shaping her own pregnant figure with a yellow egg. Kalliopi uses a red egg to create the “snake“—cutting its upright scales with scissors—while Despina opts for a green egg. Kalliopi showcases her skills with a multi-strand bread holding a blue egg—designed to be hung on the wall—another one adorned with a dough flower on the egg, and a basket containing an orange egg. Despina crafts another “beast” with a green egg.

As the bread and rings rest, the focus shifts to the alley in front of the oven, which is fired up by the pine branches. When the “panoflio” (the oven’s interior surface) turns white, it signals that the oven is hot enough for baking. Kalliopi leaves and returns with an armful of fresh green plants. “Any fresh branch is suitable for sweeping away the ashes,” she explains, “because it doesn’t catch fire.” The plants also lend a pleasant aroma to the oven. She constructs the “anenoui,” an improvised broom, by tying a bundle of fresh branches to the end of the oven’s handle. After dipping it in water to prevent burning, she uses the broom to clean the oven, stirring the coals until they settle and the oven is ready for baking.

Kalliopi pushes the ashes to the side to preserve the oven’s heat and begins placing the bread rings on the oven floor with a paddle, transferring them from the dough-shaping area. The rings quickly develop an appetizing, golden-brown exterior. Once fully baked, she stacks them in front of the oven’s opening. In the back, where the oven is hotter, she places the trays with the colorful “pouloi” (bread figures).

The “pouloi” and rings bake swiftly, while the loaves of bread and the cross-shaped rings require more time. These hard-textured loaves for Maundy Thursday are considered more ‘blessed‘ than the others. Perhaps the crosses adorning their entire surface protect them. They remain intact for months afterward, to be used during the harvest season and offered alongside olives, cheese, and water. Kalliopi prepares the cross-shaped rings with leaven, old-fashioned flour, and a generous assortment of spices: mastic, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, and freshly ground nutmeg.

Good Friday arrives. For the people of Olympos, the day of the burial of Christ is a time of self-awareness, for reflecting and remeberence of those who have passed – symbolising the origin of age-old tradition.

On Holy Saturday, the ovens are fired up again—once, twice, or even three times. In the afternoon, they bake the Easter “lambriatikes” cakes. Kalliopi makes these on Holy Saturday afternoon. In the past, this dessert was not only a delightful Easter treat with a cheese filling, but also the weekly favorite baked good for children, served before the bread every Saturday. The filling consists of two kilograms of fresh mizithra cheese, a large spoonful of dried, ground fennel, a hint of Chios mastic for aroma, one kilogram of sugar, and a small spoonful of ground cloves. For the dough, Kalliopi kneads two kilograms of flour together with a cup full of olive oil, one egg, and a cup yogurt.

Rekindling the oven with fresh pine wood is easier, as it’s already hot from being lit early in the morning to bake bread. The “kefalopoda” (goat’s head and legs) are tossed in whilst the fire is still flaming. Destined to become “byzanti” (goat soup), they turn pitch black, but as Kalliopi scrapes them with a knife, they change appearance and color, turning completely white. They are the main ingredient of the evening’s resurrection stew, known as “patsa” here.

Before placing the pies in the oven, Kalliopi refreshes the oven with branches of sagebrush to emit a pleasant aroma, just like everything else—the bread, the freshly baked pies, and later, the “byzanti,” the stuffed goat. The oven is lit for the third time in the evening to slowly cook the goat all night, ensuring it will be delectably ready by noon on Easter Sunday to serve as the centerpiece of the festive table.

However, Nikos and Marina invited us to visit another neighborhood and another oven. Marina marinates the whole lamb with a mixture of dry tomato paste, a little olive oil, salt, and spices—pepper, cumin, and a hint of cinnamon. She then rubs the lamb’s body with a lemon half. Meanwhile, she prepares the stuffing.

She sautés the finely chopped onion and small pieces of liver in olive oil, seasoned with salt, pepper, cumin, a touch of cinnamon, and garnished with a small bunch of finely chopped dill, fennel, two mint leaves, celery, one or two tablespoons of tomato paste, and fresh tomato. All these ingredients simmer together, and at some point, the rice is added to absorb the flavors.

The appearance and taste of leavened bread, with its slightly sour flavor from the sourdough starter, baked in a traditional wood-fired oven using wood from the surrounding groves, is enjoyed in every facet as part of Olympos’ way of life. Even the morning toast at Philippakis’ café in Selai is complemented with slices from a large loaf of leavened bread. As is, of course, the ceremonial bread and the Antidoron (blessed bread).

In these traditional practices, the connection to the source of food is evident and appreciated. People embrace the process of transforming raw ingredients into delicious dishes, which then become part of their daily lives and festive occasions. The rituals and flavors of these meals create a strong sense of community and a shared identity.

Just like the bread that is being blessed now at the center of the atmospheric church during the service of the Second Resurrection on Easter Sunday afternoon. This bread will be cut and shared symbolically among the faithful as the true, blessed bread of life, as is the Antidoron that priest Pap -Yiannis distributes after the end of the service, cutting the leavened bread with a knife as he offers it.

Nikos G. Mastropavlos is a journalist, creator of eudemonia.gr, a website dedicated to the culture of everyday pleasures in Greece and Cyprus. Through his work, he explores and shares the rich traditions and customs that define Greek and Cypriot culture, focusing on the importance of food, rituals, and celebrations as essential components of a fulfilling life.

Read also:

Five reasons to visit Karpathos